She Saved Him, Too

Susan Kushner Resnick was recovering from post-partum depression after the birth of her second child when she struck up an unlikely friendship with Aron Lieb, a widowed, childless, elderly Holocaust survivor. Unraveling his tragic story, enjoying his company, and caring for him in every sense of the word occupied much of her time over the next 14 years. Her new book, You Saved Me, Too: What a Holocaust Survivor Taught Me About Living, Dying, Fighting, Loving, and Swearing in Yiddish, is a poignant, funny, loving portrait of their complicated relationship. A graduate of Syracuse University and the Creative Nonfiction Writing program at Goucher College, she teaches nonfiction writing at Brown University and lives in suburban Boston with her husband and two teenage children.

“Jewesses with Attitude” [JWA] talked to Resnick [SKR] about her experience as Aron Lieb’s “soulmate.”

JWA: So many women your age are taking care of elderly parents. Do you think you could have been as patient with a difficult parent as you were with Aron? Would you have had as many moments of conflict? (For ex., "I should be with my kids, not in the ER with him.")

SKR: I strongly believe that it was easier for me to tolerate Aron's shenanigans because we didn't have the history that blood relations have. In those relationships, there's all kinds of button-pushing going on in addition to what's happening on the surface. I think we should all trade care-taking for each other's elderly parents to eliminate a lot of that resentment.

JWA: That’s an interesting idea. You talk about how your husband (who sounds like a real mensch) and your kids felt about your relationship with Aron, but you don't say if your parents were perplexed, proud …

SKR: My mother had met Aron but died several years before the heavy-lifting of caring for him began. She was a very compassionate person and a social worker, so I like to think she would have been proud of my efforts. My father had a little trouble with my dedication to Aron at first. He mistakenly thought Aron, because of his age, was a father-figure to me and that I was adopting a substitute. But of all the roles Aron played in my life, Daddy was not one of them. He was simply too needy.

JWA: You thought the organized Jewish community would help you meet at least his material needs, but that didn’t happen. Still, it was the members of your temple who came up with the money needed to get him into the nursing home. What does that say about what it means to be "a good Jew"?

SKR: Before going through this experience, I thought those people who ran Jewish institutions and held high-ranking volunteer roles in the Jewish community were the "good" Jews just because of their involvement. It made me feel like a relatively bad Jew in comparison. But after the deep disappointment of being let down by such folks, I realized I was just plain wrong about those characterizations. Being a good Jew—or a good anything—has nothing to do with affiliation or participation and everything to do with following one's conscience.

The help my temple mates gave also showed me that individuals of modest means are often more powerful and generous than wealthy institutions.

JWA: That’s why some of the poorest states in the nation—for example, Mississippi and Alabama—have among the highest scores on the “generosity index.”

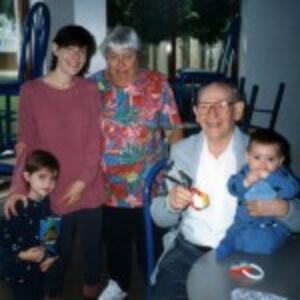

Susan Kushner Resnick's website has a gallery of photographs of Aron Lieb.