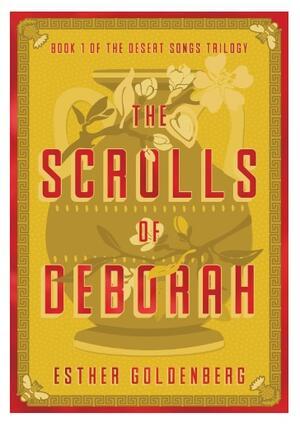

"The Scrolls of Deborah" Celebrates Women's Resilience

While the most prominent Deborah in the Torah was the only female judge in the Book of Judges, Esther Goldenberg’s new novel, The Scrolls of Deborah, presents the story of an unsung Deborah: Rebekah's nursemaid, who supported her and her descendants (particularly Jacob) in thriving. With lyrical prose, this historical fiction novel delves into Deborah's character as someone beyond just Rebekah’s nursemaid, exploring her complexities, struggles, and triumphs, as well as the many women with whom she connects along the way.

The book opens with Deborah telling her life story to Joseph, grandson of Isaac and Rebekah. “I am Deborah. Daughter of Daganyah. Daughter of Hallel. Daughter of Sarah.” Deborah immediately grounds us in her lineage, likely both to establish context for her story and to hint at the theme of female connection that undergirds it. Instead of a more formal tone, which might be expected from a story set in Biblical times, Goldenberg gives Deborah a voice that is both modern enough to resonate with readers and time-appropriate enough to pay homage to the era of her upbringing and life.

Immediately after introducing herself through this line of women, Deborah quips, “Yes, that Sarah, the wife of Abraham, to answer your eyebrow’s question.” This banter settles the reader into what becomes a fast-paced recounting of Deborah’s life, broken up into separate “scrolls” (what might be considered “sections” in another text) and “parchments” (what might be considered “chapters” elsewhere).

Deborah’s life is difficult. She experiences traumas such as the death of her mother, a miscarriage, and a rape. Yet guided by Goldenberg’s writing, the story never feels overly heavy nor dense. Deborah meets the challenges of her life with resilience. Her go-to coping mechanism when faced with a difficult situation is breathing in and out in the name of God: in with a Yhhh and out with a Whhh.

It is the themes of resilience and female solidarity that make this book particularly relevant. Reading this book now, in a period that feels politically and socially precarious to many, offers insight into how we as members of our own communities should respond and care for ourselves and others during hardship. Pain and loss may be inevitable as we navigate our lives, but Deborah offers the wisdom of meeting them with softness and tenderness that allows these challenges to flow through us, rather than be sidelined from our experience as humans.

Deborah’s openness to others and lack of judgement is also particularly striking: though not all women she encounters are Jewish or practice in the same way that she does, she never scorns them or behaves rudely. Instead, Deborah consistently focuses on what she can control: the curation and development of a community of women who routinely support one another. For example, they engage in a monthly ritual of dancing prayer to express their collective sisterly love and spiritual faith.

The deepest of the female connections that Deborah develops is with Rebekah, one of the four matriarchs of Judaism and wife to Isaac. When the two women meet, they almost immediately develop a sisterly bond and dedicate themselves to preserving their capacity to stay in one another’s lives by accepting marriages and work that will keep them connected. They do all this despite the social norms of the time that afforded them relatively little autonomy. The two have some familial connection, as Deborah is Abraham’s great-granddaughter and Rebekah is his grand-niece. But the depth of their bond stands in stark contrast to the many deep close biological ties that unravel over the course of the book, most notably between the brothers Jacob and Esau, who fight and deceive one another in order to obtain the first-son blessing. The chosen love shared by Rebekah and Deborah is not one of convenience—Deborah has several opportunities to leave of her own accord—but one of true understanding. Following a low point in Rebekah’s life, Deborah tries to cheer her up, telling her friend, “Do you think I have not smelled the wind that escapes your bottom in your sleep, or the odor of your breath before you have chewed hyssop or mint in the morning?… Have I not heard you complain for days when you bump your toe or trip over something that you yourself forgot to return to its place?” The intimacy and comfort expressed in Deborah’s words highlights the depth of a relationship that can only exist between two people deeply committed to each other at their best and at their worst.

The love shared by Deborah and Rebekah is a source of inspiration for modern Jewish sisterhood. It's a love that transcends surface flaws, allowing the women to see and nurture each other's core goodness. In Goldenberg's captivating story, Deborah and Rebekah prove that despite difficult circumstances and systems of patriarchal power, it is possible for women to create community and friendship borne of deep and reciprocal love.