The Scarlet Letter Reports

"The rest of the world is not kind when it comes to women's sexuality.”

No, it certainly isn’t. It wasn’t kind to Lilith, who was demonized for asserting a sexual preference. It wasn’t kind to “witches” in Salem, who were hanged for “challenging Puritan values.” It wasn’t kind to Monica Lewinsky, the young Jewish intern who was scapegoated to protect the powerful position of an older man. It wasn’t kind to my middle-school friend, Katie, who was called a slut for wearing a tanktop. It isn’t kind now.

2018 has been a watershed year for women. #MeToo has encouraged assault victims to share their stories and allies to support them. Abusers, who previously hid in the shadows of the industries and people who protected them, have been dragged into the light.

We still have a long way to go. Whether a woman appears promiscuous or buttoned-up; engages in consensual sex or chooses not to have sex at all; has sex with men, women, neither, or both; or is assaulted or raped, she alone is judged.

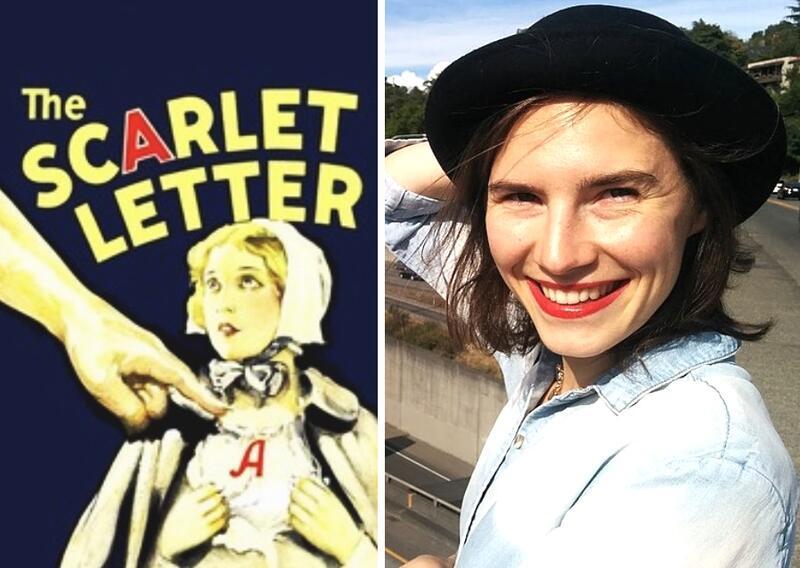

In the 2018 Facebook series, The Scarlet Letter Reports, host Amanda Knox explores this idea: that the world wields a woman’s sexuality against her like a weapon. In each episode of the Broadly-produced show, she interviews a famous woman who has been attacked or disbelieved because of her sexuality or sexual history, including Anita Sarkeesian, Amber Rose, Daisy Coleman, Brett Rossi, and Mischa Barton. Knox’s own experience of being demonized by tabloids during her 2000s murder trial in Italy clearly informs her interview style. She asks careful, compassionate questions throughout each 15-minute episode, empowering the interviewee to speak honestly and without shame about her experiences. The Scarlet Letter Reports succeeds in giving previously silenced women a voice and previously dismissed women a platform.

In the fourth episode of the series, Knox interviews Daisy Coleman, who at fourteen was brutally raped by a popular high school football player. When she decided to press charges, her classmates and neighbors turned on her instantly. Coleman, like so many other sexual assault survivors, was immediately ostracized by her community when her credible claim of rape threatened the reputation of a man. She was called a liar, a slut, a whore. The abuse became so pervasive that Daisy and her family were forced to move to a different town. Knox and Coleman discuss how the abuse she suffered after her sexual assault was almost worse than the assault itself. In her U.S. News piece, “We’re All Sluts Now,” Leora Tenebaum states, “Anxiety over women's sexual agency is so strong that even when a woman is robbed of her agency through sexual assault, she still is punished for her agency.”

In the fifth episode of the series, Knox asks Brett Rossi, who filed a domestic-violence lawsuit against Charlie Sheen in 2015, “Do you feel like anyone has ever…genuinely asked you: ‘What is your experience and how have you grown? Do people approach you that way?” “No” is Rossi’s reply. In truth, we rarely see assault victims approached in the way Knox approaches Rossi: with respect, empathy, and a willingness to believe. Perhaps that is why it’s so jarring to hear two women have a frank conversation about sexual violence: it’s so uncommon.

Later in the episode, Knox asks Rossi another question: “Has anyone ever approached you from the #MeToo movement?” Rossi’s response is again “No.” She explains: “It was automatically assumed that I was a liar, even though the person that I had this suit against had a thirty-year history of…abusing women, being convicted of abusing women.” Rossi emphasizes that people, even people from the #MeToo movement, cite her profession to discredit her: “I am a pornstar, a sex symbol. I’m disgusting. I’m pathetic. When you hear people tell you what you are so much, every single day…you start to believe it.” Although the women Knox interviews have unique experiences and have been impacted by sexual harassment and assault differently, almost all of them echo Rossi in describing how people’s perceptions impacted how they saw themselves.

Needless to say, this episode, and the series as a whole, is heartbreaking and at times difficult to watch. But, it’s also important and eye opening: as Rossi tells her story and references how gaslighting warped her sense of self, the shortcomings of the #MeToo movement become evident. Many women (and men and non-binary folks) have been left out of the conversation: sex workers, adult film actors, pornographic magazine models. Why? As Rudy Giuliani said at a recent conference in Tel Aviv: “I don’t respect a pornstar the way I respect…a woman of substance…a woman who has great respect for herself.”

Unfortunately, this sentiment that certain women are not worthy of respect permeates popular discourse about sexual assault in even the most progressive circles. By interviewing famous women shamed by the media for this very reason, Knox aims to undo the thinking that the way a woman engages in sex (or doesn’t) is tied to her respectability, self-worth, and right to be believed. In Hannah Gadsby’s recent Netflix special, “Nanette,” Gadsby speaks to this slow, but sure, societal shift. “Do you know who used to be an easy punchline?” she asks. “Monica Lewinsky.” Used to be. She’s not such an easy punchline anymore.

"Believe Women." With a simple message,The Scarlet Letter Reports strives to ensure no one’s #MeToo story will ever be used as fodder for an insult or a joke again.

Believe women. I certainly do.

If you have experienced a #MeToo moment, we invite you to share your story with the Jewish Women's Archive through our Archiving #MeToo project.