Wonder Woman's Hemline

After spending time in communities where people define their feminism so differently, I have come to claim my title “feminist” as a woman who supports choices and respect for women. It took time for me to grow confident with this definition because I’ve felt confused when considering my Judaism and feminism together.

While spending a semester in Israel, I was challenged to reaffirm my definition of feminist. As one of the people on my program who’d had more exposure to religiously observant Judaism, I often found myself representing the more traditional, textual Jewish perspective for my program, though never as strongly as on a particular outing to the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Mea Shearim. In Mea Shearim, women must dress modestly (or tznius) covering elbows, collar bones, and knees.

As we were getting dressed to go, a classmate asked me, “Can I wear earrings?”

“Of course, why not?” I replied, confused.

She responded, “Well, they kind of look down on style there.”

I was stunned and upset by her use of the word “they,” as if observant Jews are a different species, distant and bizarre. “They” are us. She’d acquired a misconception that all religiously observant people look down on style; many observant families, however, take pride in stunning Shabbos tables, elaborate simchas, and gorgeous matching children’s outfits for Shabbos and holidays. I attributed her statement to a lack of exposure.

When I was nine, my dad moved to an Orthodox neighborhood in Cleveland, Ohio. Living primarily in a Conservative bubble in Charlotte, NC, when I flew to Cleveland every other weekend I was dropped into a different world, one where girls didn’t wear pants or go to school with boys and where the laws of the Torah guided every aspect of life. It didn’t feel like my world and being there, I didn’t feel like me. I was suddenly “Cleveland Lilah” who couldn’t wear shorts to walk to the mailbox. I thought that if I was supposed to respect the religiously observant neighbors’ custom of wearing modest clothing, they should respect my custom of wearing shorts! I resented that I had to change myself for “them” and “their” rules.

My female classmates were angered by having to wear long skirts to enter Mea Shearim, while the boys could wear whatever they wanted. Initially, their objections seemed like those of any logical feminist. In part, I felt that if I was a feminist, a liberated woman, I should have been upset too. I’d felt a similar frustration to that of my classmates when I was younger in Cleveland. However, I was not upset. In fact, I loved the excuse to dress modestly (though I know I shouldn’t feel like I need one).

Sometimes I’m uncomfortable wearing a long skirt because of assumptions people make about my identity. For me, seeing my classmates in tznius outfits didn’t change their identities; they were still their unique selves, just wearing different clothes. While they discussed how women in this neighborhood were “oppressed", "forced to be mothers", "confined to traditional gender roles" I yearned to say: “Is it not possible that they want that life for themselves? It may be forced on some, but is it fair to assume it is forced on all?”

My cousin grew up as a secular Jew, but now lives a strictly religiously observant life in Jerusalem’s Old City. She told me that she finds covering herself empowering, and the fact that a strand of her hair or an inch of her skin could attract a man speaks to the power of a woman’s body. She believes that men don’t need to cover their bodies because they don’t possess the same power as women. Wrapping herself up strengthens her self-esteem and functions as a reminder that her body is too precious to be displayed for all to see. Her perspective affirms that honoring a certain code doesn’t strip a woman of her freedom or femininity; nor does breaking it. Similarly, my choice to honor someone else’s code out of respect doesn’t weaken my own personal code.

Hearing the comments made by my classmates in Mea Shearim reminded me how much my perspective has changed. I sympathized with the views of my friends who felt the way I originally felt in Cleveland: wanting to not wear a skirt out of pride rather than wear a skirt out of respect. I now know that respecting others can coexist with doing what is empowering to me. I know it isn’t about me, and it isn’t about anyone trying to change me. It’s about respecting a community and home. I am confident enough in my beliefs to honor someone else’s customs in order to show respect. I believe that sometimes you must value someone else’s comfort over your own.

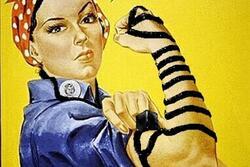

Some women find wearing long skirts empowering and some find wearing shorter skirts empowering. Both should be respected. There is no superior female warrior. Power comes from choosing for yourself, rather than hitting default. I recognize that I am privileged to have choices. I love the humanities and want to be a mom one day. I have no intention of apologizing for fitting female stereotypes, just as I don’t want any woman to apologize for not doing so. The “right answers” as a feminist are the ones that are your own. Wonder Woman’s power doesn’t come from her outfit. It comes from the power she claims, and the actions she takes to define herself. I am thrilled to have found my definition of feminist: a woman who supports choices and respect for all women. The length of your hemline doesn’t matter as long as you choose it for yourself and you accept those who choose differently.

If you are looking for more information on tznius, there are some great articles related to this topic.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.

Yes! Claim your power!