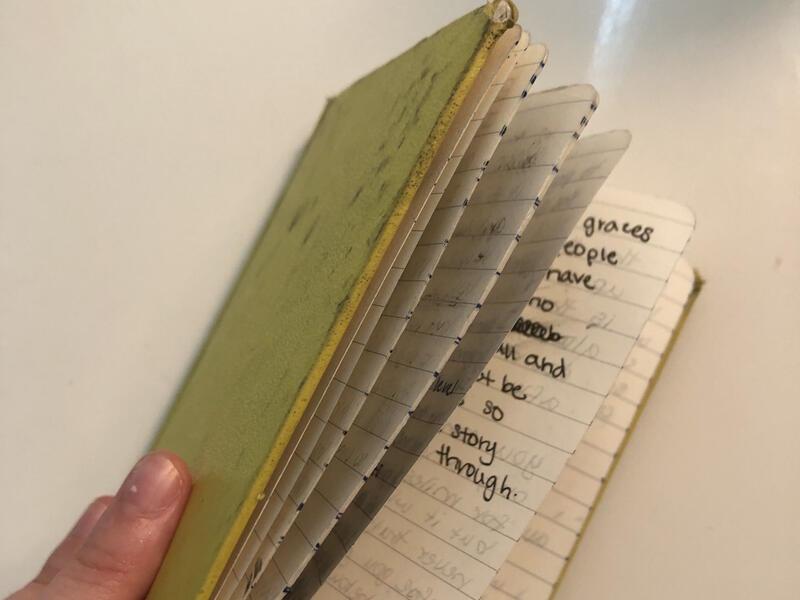

My Worn and Faded Yellow Notebook, a Living Record

In my backpack, I carry that artifact commonplace among people who yearn to write. That four by six rectangular prism containing 100 miniature pages, each with 23 thin horizontal lines, shrouded in a folded strip of yellow cardboard and encrusted on all sides with blotches of smudged black ink. A dirty notebook, worn and half-full, plucked off the store shelf in a small moment of ambition, or maybe some other hunger of the soul.

I carry this writerly token, which has undergone a series of rapid transformations, slow evolutions, and periods of lapse in usage over the years since its acquisition, but which now functions as a supplement to my memory, a record of passing comments and observations and reactions whose weight I will remember but whose details might fade absent this paper register. These are the catalogs of daily life, my daily life, bits and pieces dictated by the here and now of an American society that remains ever tinged by the past, though many may live unconscious of its mark. So notebooks look upon this society with conscious eyes. Notebooks leave an indelible impression on the collective memory of the era in which they were written, and the influence of the eras that came before. And in my notebook, I recount the anecdotes that bear the mark of the past I am reckoning with today. My notes often begin with a place; in particular, a place that makes visible our social tensions.

Here is an essay in waiting: ‘River Oaks at Christmastime.’ The spectacle that is all the diverse ‘tourists’ from around the city, creating stand-still foot and car traffic as we all pose for pictures and gape up at the opulent lights.

River Oaks, the wealthiest Houston neighborhood, boasts mansions that compete with the White House in grandeur. It’s a neighborhood that, of course, prohibited Black people and Jews from residing there for decades in the 20th century, and that now attracts the rest of the city to observe its winter wonderland from the sidewalks, glimpsing this ever unreachable life.

I write of places that develop new exteriors over time, always feeling the power of the years of exclusion and trauma beneath, still unresolved:

This couple new to Houston who we invited to Yom Kippur break fast told us they passed by the JCC and momentarily mistook it for a prison. Really, I can’t blame them, what with the endless gates and barbed wire and bollard car bomb barricades and massive slabs of grey concrete.

In addition to observations of the places themselves, I record moments where people and place converge:

Today, V [my Muslim best friend] dragged me to the ‘faith-inspired clothing store’ she loves to shop at, which we’ve christened ‘the Jesus Shop’. She texted me afterwards ‘thanks for coming with me to the Gesus [sic] Shop!’ I laughed reading this, thinking that sometimes resisting American assimilation manifests in the unwitting irreverence towards our lord and savior that occurs when two kids show up together in a place created for neither of them.

I love the irony of our presence in this shop, this “irreverence” towards a figure, a culture that commands national public life. Our casual “irreverence” at the Jesus shop reminds me of another note, where youth intentionally challenge the principle of unwavering respect for establishment ideals and leaders:

At any climate activist gathering, I’m always impressed by the de facto uniform of combat boots we all know to wear as we arrive for protests at government buildings. I guess this means we want battle, battle at esteemed institutions of professionalism and unquestioned authority, or, at least, that’s what we’ve been driven to.

I feel an overwhelming, even cathartic urge to record these observations because when people enter places they have clashed with in past decades and generations, a story unfolds, as the history of struggle and exclusion reveals itself. Like in any literary tale or tradition, the setting and the plot serve as conduits through which the underlying themes emerge, but so do the oft overlooked details. Like any symbol, within the supposed smallness of the detail—the misspelled words, the tattered boots—lies the significance of the grip of the past on the present. Jotted down in a notebook, the details thrive. After setting, plot, and symbol, we need dialogue to complete the stories transpiring around us. I listen to people and their words, the conversations that take unexpected turns, steered sharply by the past:

My mother is rambling about the Nazis again. Today, after we watched a high-anxiety and depressing movie that featured war-inflicted death, tears streamed down her cheeks as she insisted we not watch any more heavy content while she [a healthcare worker] copes with COVID-induced stress. What began a straightforward, albeit emotional, request teetered off into incoherence, landing somehow, suddenly, at an insistence that I remember how it really was not that long ago that ‘they were rounding up Jews.’ She insists that it could just as easily be her father—a man born in Nazi Hungary—living in our home with us through this pandemic, and not her mother, born in safety. I am speechless because I do not know where this seemingly random stress is coming from. But of course it is not random—growing up with conversations of the camps at the dinner table, that anxiety always awaits an opportunity to resurface.

And sometimes, the conversations morph into past actions that haunt us:

When that scene on the new TV series comes on, when the 70s-era teenager gets into a fist fight when called those antisemitic slurs, when I become captivated by the anger I recognized on the screen, my mother wants to flee from the room, she admits at the end of the episode. She tells us she remembers the time another child wielded a knife to chase her seven-year-old self through a small town in 70s Pennsylvania. The story of a child who does not yet understand hate, but who finds herself staring down violence taught to another child too young to comprehend his actions. The story of a little Jewish girl running, my Jewish mother still running.

Do I run from the story? No, I choose to write the story down.

I stay put; I remember.

I write about these moments because they demonstrate the daily experience of someone like me, someone who can recognize themselves in any facet of my identity: Generation Z, Jewish, American, young woman, living in a major city with oppression in its midst. I bleed politics and social norms and history, institutional and familial. I see the story in the moment, and I hope to one day write these moments into long form essays in an attempt to reveal how history is ceaseless; the past does not remain in the past, not for someone who wears history so heavily. But for now, I remember these moments in the pages of a four by six, ink-smudged, faded yellow notebook, a humble place for these compelling moments to live, awaiting the future attention of a fully written story.

In each generation, the story manifests differently and writing—and journaling—allows us to learn the implications that history has on the present population. Writing brings consciousness, and consciousness arouses social good. The moments I record are small but the project is infinite. Telling stories of life and identity forged in the present, stories that are but the next iteration of the tradition of telling stories of life and identity that depict the human condition and generations in the making.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.