Her mouth opens with wisdom, and words of loving kindness are on her lips

Laws, tradition, and God are words that typically come to mind when you think of Judaism. In my Bat Mitzvah parsha (Torah reading), Lech Lecha, these words are relevant, but not the ones that stuck out to me.

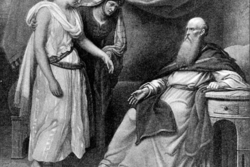

The portion covers Avraham and Sarah, Judaism’s founding patriarch and matriarch, on their journey to Canaan. While they travel through Egypt, Avraham tells Sarah to lie and say that she is his sister. He does this because she is so beautiful that he’s worried that the Pharaoh will want to kill him and take Sarah as his own.

This idea of a woman’s beauty—and beauty in general—in the context of Judaism was something that caught me off guard. Although I was a middle-schooler, and obviously thought about beauty and how I looked every second of every day, those contemplations never crossed over into how I thought about Judaism.

This newfound fascination with the notion of beauty in relation to Judaism inspired me to go exploring. It turns out that the Torah doesn’t actually give any physical description of Sarah, so we are just supposed to trust a loving husband’s view of his wife. However, there are two more sources that point to Sarah’s beauty. Later in the same chapter, it says that the Egyptians did indeed see her beauty, and she was taken back to Pharaoh’s palace. It seems as though Avraham’s original intuition was right, but God plagued Pharaoh, and Sarah was returned to her husband. In addition to this confirmation of her appearance, she is given a head-to-toe description in Dr. Yigael Yadin’s translation of the Dead Sea Scrolls. It says,

“And how beautiful the look of her face…And how fine is the hair of her head, how fair indeed are her eyes and how pleasing her nose and all the radiance of her face…Her arms goodly to look upon, and her hands how perfect…Her legs how beautiful and without blemish her thighs. And all maidens and all brides that go beneath the wedding canopy are not more fair than she. And above all women she is lovely and higher is her beauty than that of them all, and with all her beauty there is much wisdom in her…”

The Dead Sea Scrolls contain about 40% biblical text, but this seems to be from the time of the Second Temple. Clearly, other rabbis also wanted to fill in the information about Sarah’s physical beauty. The detail and idealization of her body shows just how important looks were to how others viewed Sarah’s identity. I wonder if Sarah also found her image essential to who she was, or if it was just a value placed on her by those she interacted with.

After learning about Sarah, I wanted to investigate this theme in the rest of the Torah, and within Judaism as a whole. As it happens, only two out of the four matriarchs, Sarah and Rachel, are characterized as beautiful. The main Jewish tradition having to do with beauty, Hiddur Mitzvah (beautifying a mitzvah), doesn’t even apply to people. This commandment puts an emphasis on appreciating beauty when it enhances Jewish life, like decorating a Sukkah or putting Mezuzot in ornate cases. Instead of the value for beauty being placed on people, it is placed on our relationship with Judaism.

In exploring this topic of beauty, I repeatedly found references to Eishet Chayil (“woman of valor”), a hymn typically sung on Friday nights that is thought to be a way for men to thank their wives for the work they do in the home. In the acrostic poem, the Eishet Chayil is accredited with these characteristics: she is a hard worker who “looks after the conduct of her household and never tastes the bread of laziness;” she is generous and provides for others because “she opens her hands to the poor, and reaches out her hands to the needy;” she is wise and insightful through opening “her mouth with wisdom, and a lesson of kindness is on her tongue;” she is optimistic and loyal as “she smiles at the future…her children rise up and make her happy, her husband praises her;” and “many women have excelled, but you excel them all.” Eishet Chayil aims to describe the perfect woman, but one piece that is crucial in today’s society is missing: physical beauty. What seems to be most important in Judaism is the actions that a woman takes, not her outward appearance. Albeit most of these actions have to do with more traditional female roles like housekeeping and childbearing, the absence of beauty almost makes this hymn feel progressive in a way.

Interestingly enough, there is also a midrash (a rabbinic commentary or story) that Eishet Chayil was composed by Avraham as a eulogy for Sarah. Earlier in the story, Avraham specifically praises Sarah for her beauty. After her death though, he seems to care more about what was on the inside.

Although many years have passed since reading about Sarah at my Bat Mitzvah, the lessons I’ve learned from my exploration into beauty have stuck with me. It’s interesting to know that Judaism appreciates attractiveness; if not in a person, then in objects or traditions that relate us to our Jewish beliefs. However, in a world where we are constantly bombarded by beautiful people—mostly women—in advertisements, on TV, in magazines, or listen to songs about them, it is comforting that Judaism also values the Eishet Chayil, women who work hard and stay true to their values. That is who we should strive to be. What should matter most to us is what we contribute to this world and to those around us. And—hey you, my valor is up here.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.