“Good Humans”: Leading a Mini Feminist Revolution as a Camp Songleader

Spending summer Shabbats in my Jewish overnight camp’s prayer grove, framed in the beauty of the setting sun, pine trees, and warm community, I always felt a peaceful connection to Judaism beyond what I experienced at home. The upbeat camp tunes and lively hand motions brought a unique joy to the practice of Shabbat and prayer, one that made ten-year-old me eager for Friday night services. As several summers went by, however, a few lines in the spoken prayers began to bother me, including “Good men will grow strong like the cedars of Lebanon,” and, “He takes delight in his pleasures, like strong men running a fast race.” I found myself questioning: Why does our liturgy center men? Is it a core Jewish belief that only men could be strong, athletic, and rewarded for good? My prior Hebrew school learning about Judaism’s traditional separation of men and women and the fact that both my camp service leader and the rabbi at my synagogue were men all provided some plausible reasoning for these exclusionary lines; still, I was frustrated and craved change.

Hearing these words uttered every week, I would glance around me, wondering if any other girls were having similar reactions. I found no luck there. I tried to volunteer to read the prayer one week, hoping I could change the words in front of camp in feminist protest. I didn’t succeed; the Shabbat prayer sign-up meetings were surprisingly competitive. Feeling defeated, I somewhat gave up my tween quest for edited prayer books. I was too timid to confront anyone of authority, so I decided I would pursue connecting with the service through the stunning music and setting.

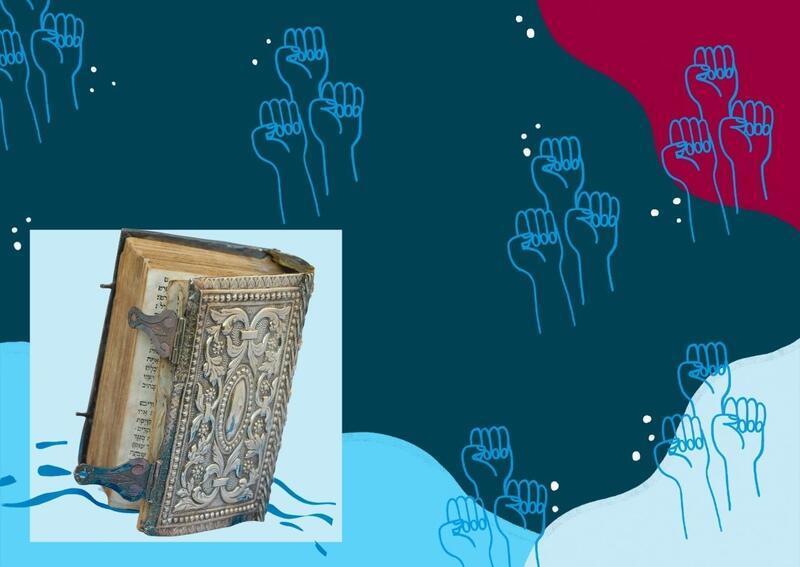

Skip ahead a few years to summer of 2021: the passionate but timid camper now finds herself a bunk counselor and head song leader. After the first few services, I found myself again drawn to consider the places in the spoken prayers that previously brought me such discomfort as a camper. With my new position of power in services, I felt a pressing obligation to change the language in the prayer books—I wanted the young girls listening to prayers to feel included in the service, community, and in Judaism as a whole. Even though within Judaism there are many male-centered practices and traditions, women can add, and have historically added, so much significance to our culture and faith. I wanted this to be reflected at my camp, starting with the prayer books we read from. Wishing to see this shift and feeling empowered by leading services all summer, I confidently approached my Judaica director after Saturday morning Shabbat services with a simple question: “Any chance we could change the exclusive language in the prayer books?” To my surprise, he was very receptive to and excited by the idea.

Hoping to include other young women in this movement (and not wanting to rewrite all 500 prayer books myself), I mobilized a squad of fourteen-year-old feminists. I was leading a music period with the second-oldest age group, and decided to float them the idea, thinking some of them might prefer change-making to singing on that particular morning. As I explained my discomfort with the prayers and wishes for change, I was met with “Oh yeah, I noticed that one time,” and, “I never thought about that––yeah, let’s do it!”

Together, we set up a little change-making station, lugging the giant box of prayer books over to the picnic tables and gathering all the black pens we could find. We crossed out “good men” and “strong men” with bold strokes, neatly printing “good humans” and “strong people” in their places. With piles of books scattered around us, we reflected on how both the prayer books and camp as a whole desperately needed change. I heard the same injustices shared that had bothered me as a camper: girls not being respected in sports games, minimized to making friendship bracelets, etc.

Experiencing camp through the framework of a counselor, I held my own beliefs about where camp should transform: heteronormativity, toxic hookup culture, difference in counselor treatment and expectations for girls’ bunks and boys’ bunks. Making space for this conversation felt like one step toward addressing larger structural concerns, and provided young feminists with an opportunity to begin to see their power.

That Friday marked the exciting debut of our renovated prayer books. As a service participant read “good humans” in place of the usual “good men,” the camp responded with a mix of scattered claps of approval and cheers from the young women who had helped, and some newly-motivated counselors and campers. As I watched my campers’ faces light up, I felt a rush of excitement, fulfillment, and power. I knew that I had sparked the prayer revision, a goal of mine since I was a young camper. Now, others had the chance to see themselves reflected in our prayers. All it took was one vocal counselor, and suddenly, a whole bunk of campers was engaging with feminism, meaningful conversation, and tangible action.

We couldn’t fix every sexist aspect of camp in that one sitting, or even in one summer. The simple act of replacing words in the prayer books wouldn’t address the larger structures of sexism at play at camp—in counselor treatment, toxic hookup culture, camper activities—or in the Jewish religion. But we had made a real difference, even if that difference just started with changing the words in our prayer books.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.

This was a great article that addresses issues within religion (and society) as a whole. I don't personally believe that men and women are the same, but I do view myself as a feminist. Women deserve to be treated equally and with respect. For example: where a man (in general) has greater physical strength, a woman (in general) has greater strength of emotional understanding. Both genders have their strengths and weaknesses, with neither being completely superior to the other. Whatever your orientation, sharing and complementing another person's strengths and weaknesses makes a better community and a better world. We just need to make sure everyone is viewed as equal and given a fair chance. Books and religious texts written in a time period where men held most or all of the power are like history books- skewed in the biased direction of the winner/writer. That doesn't mean nothing inside is good or right, only that we need to bring the teachings into a more equal society. If we as a species are still here with the same religious beliefs in a century, I hope that the texts are edited to reflect new knowledge that humanity should have. This same concept goes for everything- governments, laws, international and national communication, etc. Anyway, this was a positive and encouraging article that I hope is read by many people in the Jewish faith and other faiths as well. Thank you, Talia Bloom for your insight and the encouraging changes you're helping to create!