The Elements Of Style

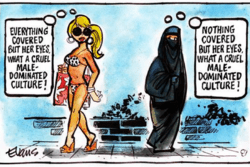

Every single morning, I wake up, shake the fog out of my head, and consider what I am going to wear. Almost every day, my outfit is some version of Doc Martens (or, “Docs”) boots, a white button up shirt, and jeans. I somewhat intentionally do not dress like most of the other girls in my grade. I don’t care about looking similar to them, but I do care about my appearance. One of the frequent questions I’ve gotten when talking about my feminism is, “Don’t feminists not care about clothes?” It’s true that second wave feminists, who were fighting for women’s full inclusion in society, rebelled against traditionally feminine garments, most notably bras, and protested fashion based institutions. So, I often reply to this by quoting the fabulous Solange Knowles: “Fashion is nothing to me, but style is everything.” It’s true. Fashion is the twice-yearly shows replete with journalists, models, and industry hopefuls dressed to the nines. Fashion is furry sandals, clutches that look like boxes of cereal, and silk pajamas that women wear because a designer (usually a man) has deemed them “in.” Fashion, as much of the world sees it, is a narrow subsection of the world, and the industry’s history as it pertains to inclusivity, is patchy at best and appalling at worst. Style is much more than that. While fashion is a pendulum representing a given label’s whims, style is timeless; it’s the way we put ourselves together on a daily basis-- how we dress for battle.

So, do I care about fashion? No, not really.

Trends are something that I observe in magazines and consider the origins of, but I do not adopt them for myself. This does not mean that clothes are insignificant to me-- quite the opposite in fact. I dress with absolute intention, wherein each of the elements of my style serves a very particular purpose, but their significance in fashion is fairly negligible to me. Take white oxford shirts, for example. They’re regarded in the world of fashion as a perennial classic and as a way to “borrow from the boys.” For me though, they provide a feeling of professionalism and an essential boost of confidence when I’m resolving issues on my newspaper or working out a problem in front of a crowd. I wear them not for their clout in the magazines, but for their look and their intellectual feeling. I am sometimes painfully aware of the politics that come with wearing clothes that were traditionally meant for men, the only recognized academics for much of history. I worry that these clothes imply that I aspire to the traditional, male-dominated terms of success. On the contrary, I hope that my adopting elements of menswear is construed as a subversive redefining of the traditionally ‘intellectual’ look. Docs invite similarly defiant historical connections, having been the well-documented chosen footwear of countercultures such as the punk and grunge movements. In their heydays, these movements revolutionized the “mainstream” in manners of fashion, philosophy, and otherwise. I hope to one day join the ranks of these cultural pioneers. Maybe I won’t turn the world upside down as they did, but I might at least turn it sideways. Styling myself similarly to them creates a link in my head between myself and them, no matter how superficial it may seem. Until I am one of these movers and shakers, I can at least dress as they do.

Docs also bring me back to my thirteen year-old self, who was finished trying to fit in and used these shoes as her first rebellion against the sartorial norm. Little did I know that this initial action against convention foreshadowed an emerging theme in my school life, where I was quickly becoming the class nonconformist. Recently, though, I started to feel as though my clothes projected a louder statement than my voice did. The way I had been dressing clearly signaled my intentions, but also limited me in a way-- I found that people set expectations for me based on what they saw, rather than what they heard. I then had to figure out how to dress in a way that made me feel creative, in control of my image, and still expressed my identity as a proud rabble-raiser. I found an answer to this dilemma in the incredible book, Women in Clothes, in which contributor Christina Muhlke says, “At a certain point, I realized it was more punk to dress like a ‘normal’ person and infiltrate the world from the inside than to have everyone treat you like a freak.” Taking this to heart, I pared my wardrobe down, finding that dressing in a more pedestrian way helped me to direct focus to my ideas. The writer, editor, and actress Tavi Gevinson, another Jewess with some serious attitude, also discussed simplifying her style, saying, “it's nice to just wear the stuff that makes you feel good, so then you can go about your day and put your energy into making other cool stuff.” Clothes became another component of my “toolbox”-- rather than just being a series of aesthetic choices, the way I dressed could help me accomplish something; the elements of my style could help me better execute my missions in life, and give me the courage to be the person I want to be.

These days, I look “normal”... almost. I wear ordinary things but they all share a crucial component: they are the classic attire of thinkers, innovators, iconoclasts, and the all-around fearless. This is how I hope to be seen as a feminist activist and writer-- thoughtful, confident, and breaking new ground. And I wear these clothes with intention-- every element of my style is meant to give me the guts to smash barriers and help others. Isn’t that what feminism is all about?

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.