Dear Betty Friedan

Dear Betty Friedan,

Since I was little, I've always been taught that questions are a good thing. “Inquisitive” was my favorite five-dollar word, and my hand often shot up in class in search of more satisfying answers. When I first learned about you while researching second wave feminism for a paper, I marveled at how one woman could inspire so much change. Astounded, I looked deeper and realized results sprang from your willingness and determination to ask questions, and your dedication to and passion for finding answers.

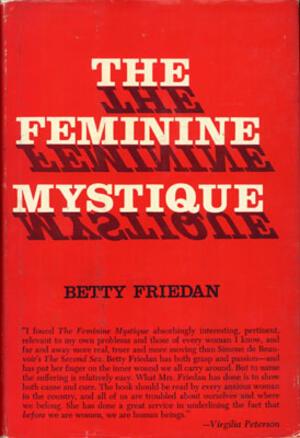

In my research, I found books like Stephanie Coontz’s A Strange Stirring which provided me with more context about you and the world you sought to change. I read about a 1950s culture that encouraged white middle class American women to define themselves through their roles as mothers, wives, and homemakers. Education and careers were secondary, and often even discouraged. It surprised me to learn that women who wanted a career were deemed “un-feminine” because a “normal” woman would only want to get married and help her husband succeed. I was also surprised to find that it really seems like women submitted to this restrictive social pressure; it was standard, little had been said or done to change it, and no one had the words to describe it (until you deftly named it The Feminine Mystique).

I find myself wondering: If I were living in the 1950s and was told that my main goal in life was to find a husband, have kids, and take care of the household, would I have questioned it? I like kids and pretty dresses, but those certainly aren’t the only things I like. I like to think I would have questioned my limitations; I certainly do now. I frequently ask why I can’t do what I can’t do or how I can achieve what others say I can’t. But is this just because I was raised in a world where I was told I had “infinite opportunities”? My mom went to law school, worked as a lawyer, went to school for fashion design, started a clothing business, and then had kids. With my mom’s life arc as precedent, the opportunities really do seem endless.

It’s hard for me to fully understand how dramatically things have changed. I can only imagine how women during the 1950s may have felt guilty and selfish for dreaming of any career, and were scared not only of being able to handle a career but succeeding in a career and “ruining their children’s lives as a result.” If I grew up when you did, it’s more likely that I would have been told that I had “infinite opportunities as a mother.”

I was surprised to learn that you yourself turned down a prestigious fellowship because your boyfriend, jealous of your success, made you choose between your career opportunities and him. This seems uncharacteristic of the woman who spoke out against these pressures in The Feminine Mystique. But that makes it all the more real. You weren’t immune to the feminine mystique; in fact, having encountered and inadvertently accepted it, you knew it as well as anyone.

Is this what inspired you to write The Feminine Mystique? You saw the problem and committed to sharing a solution; by suggesting that women be educated and have careers, and that marriage and motherhood shouldn’t be the only part of a women’s life plan, you revolutionized the way women viewed themselves and their purpose in life. The Feminine Mystique normalized women’s ambitions and gave them the confidence to follow their aspirations and pursue their passions. Women credit The Feminine Mystique as the catalyst that pushed them to go back to school or get jobs. The phrase “feminine mystique” helped women describe how they were feeling and being treated.

You made an incredible impact by questioning your surroundings, questioning your own actions, figuring out a solution, and bravely sharing it with the world. Your seemingly benign proposition was radical during the 1960s, and your ideas shook how middle-class white American women had been living for decades. This was an extraordinary achievement; yet, this work can’t end there.

You emphasized how the women’s struggle is two-sided; women doubt themselves and their potential, and external barriers keep women from reaching their full potential. Neither of these forces have gone away; they’ve simply evolved into different challenges that are on me and my generation to face.

I also can’t celebrate this change and my newfound opportunities without recognizing that those opportunities still don’t extend to large populations of people. The Feminine Mystique changed the lives of thousands of women, but it also only focused on the narratives of a certain group of women.

Your achievements remind me that there is still work to do. Your achievements inspire me to zoom out and see what I myself am susceptible to. You disconnected yourself from what you knew to think critically about society. Your actions remind me that, just because I am involved in something, be it a system, group, or movement, it doesn't mean that I should not question it; in fact, it’s all the more reason to question it. To support something shouldn’t mean to ignore its flaws; it should mean seeing its flaws and seeking to correct them.

Every good dystopian novel is about a character who questions the system. In this way, you, Betty Friedan, are like my favorite characters: Katniss, Tris, Jonas. Except of course, you are real. The change you provoked was in the world I live in, not an imaginary world of books, and your actions have shaped the way I’m able to live my life. We have a responsibility to question the world around us, and to push for better for ourselves and for others.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.