Ancient Egypt, Nazi Germany, and High School Classrooms: Is There Such a Thing as an Innocent Bystander?

"Above all, the prophets reminded us of the moral state of a people: Few are guilty, but all are responsible." –Abraham Joshua Heschel, the Prophets

There is little more frustrating than being punished for something that you did not do. The extra homework assignments because a few classmates were talking, no sandals to work because one girl stubbed her toe, no more school-wide pancake breakfasts because one group of students did not clean up their lunch, the trampoline is off-limits because one person couldn’t follow the rules. So many instances when one person, or one small group of people, ruined it for everybody.

Sometimes, the scope of the consequence can extend beyond just a school environment. When the horrible tragedy occurred on September 11, 2001, the United States as a whole was impacted in so many ways—one of the more tangible changes was greatly increased airport security. In this case, one group’s actions had ramifications that affected an entire country.

Should this be the case? I’m not saying that airport security is a bad thing, but I would like to point out that the overwhelming majority of frequent fliers do not need to be screened for explosives in their water bottles or knives in their socks. Why give every person a punishment when only a few are at fault? I feel this in my high school all the time: at the start of class one morning, my classmates and I were chastised for constantly being late–while the people who really needed to hear the message were actually not present, because they were, well, late.

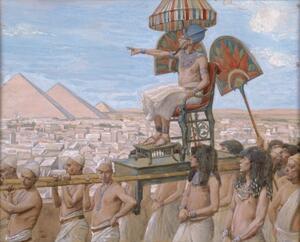

The quote by Heschel reminds me of the biblical story of how the Jews were slaves in Egypt. When Pharaoh refused to let the Jewish people go free, all of the Egyptians were punished for his actions. Tenfold. Maybe the Egyptian potentate needed to see that his own people were suffering, needed to hear the pleas from his own people, in order to realize the extent of his actions. Pharaoh was the only truly guilty one—while his fellow Egyptians may have also helped to enslave the Jews, they only did so because they had been commanded to do so. This becomes clear by the end of the story: when Pharaoh finally does agree to let the Jewish people go free, his people do not contradict him.

The way Pharaoh acted when the Jews were enslaved in Egypt shares striking similarities with the actions taken during the Holocaust. One ruling party changed the course of history for the worse. But here, there is some ambiguity. Are the soldiers who were merely taking instruction and the citizens who were only following the rules of the government responsible, too? Adolf Hitler was clearly the mastermind behind the atrocities of World War II, but that is not to say that the responsibility of the horrendous deed lies on his shoulders alone.

Is there such thing as an innocent bystander? Could the Egyptians that didn’t protest fall under this category? Perhaps so; it seems unlikely that the ruler of Egypt would have listened to them had they spoken up. Should the people of Germany who didn’t participate in the crimes of the Holocaust be blamed for something that they didn’t do (an act of omission, rather than an act of commission)? When I think of “guilt,” I see a person who did something wrong. But perhaps “guilty” should also represent a person who simply did not do something right. And if this is the definition of guilt, then any person who notices evil and does not try to stop it is at fault. I’m not saying this is fair, or just, or even accurate. But this concept does embody Heschel’s idea: few may be guilty, but all are responsible.

Although Heschel's intended meaning is ambiguous, I like to think that his intention was this: Although a few people might be guilty of doing something wrong, all of society is often responsible for creating the conditions that allow that wrong to be perpetrated. Hitler was successful because German society was receptive to hearing his message. Pharaoh was able to take power because the Egyptians gave him that power. It’s hard to think about who receives communal authority, because that power is not given by just one person. We should not think of society as a single unit, an unthinking mob. Rather, we must recognize that society is made up of individuals, and acknowledge the responsibility that each person carries to help shape a society that is ethical, just, and good.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.

Yes, Eliana, I totally agree. In these moral instances, sometimes people need to be taught to recognize the evils, then taught how to effectively protest and act to stop them them.

Great blog.

Abuela