Revisiting Israel

I am on my way to Israel for the first time in 25 years. I lived in Jerusalem for a couple of years during my childhood, but have lived in Toronto since then. I’m going to Israel with my partner, Jessie, and daughter, Ma’ayan. Both Jessie and I have mixed feelings about our relationship to Israel in the current political context. Yet, when Ma’ayan turned five, I felt a longing to take her there and show it to her, a place where she could hear her name pronounced correctly.

Tel Aviv

After a ten-hour flight from Toronto we land in humid, palm-tree-laden Tel Aviv. We have timed our visit to coincide with my father’s annual conference in Jerusalem and we will be meeting him tomorrow to visit David Ben Gurion’s house. When we arrive, the guide shows us that Ma’ayan can use an iPad to search for artifacts in the different rooms and look up related information about Ben Gurion’s life. Jessie helps Ma’ayan use the iPad as I wander through the rooms: His house is spare, the rooms decorated simply.

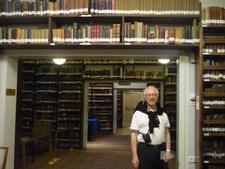

“Look at all the different books he read!” says my father, impressed by the library occupying the whole second floor. There are National Geographic magazines and books about neuropsychology, Jewish history, and Polish literature. He was well versed in several languages.

“He read so widely, and even though he wasn’t religious, he always kept a bible on his bedside table,” says my father, pointing. My father has always been observant—he goes to synagogue every Shabbat, and prays three times a day. He’s also a scientist, famous in his field of psychology for his research on memory. It makes sense that he would admire Ben Gurion’s intellect, his worldliness, and his connection to Judaism and religion.

After we visit his home, I read that Ben Gurion was tenacious in his quest to persuade the British to create a Jewish State. His diplomatic negotiations with the Germans caused them to donate so much money to Israel in reparations for the Holocaust.

In a showcase in one of the front rooms, I find the actual hand-written letter he wrote to the British government advocating for a Jewish state. His arguments cite the Jewish people’s biblical claims to the land. There is no mention about the rights of the Palestinian Arabs who already lived there or of their claims. This surprises me for some reason and illuminates the problems that are so evident in Israel now. I try to talk to my father about it, but he argues that once the state was created, Ben Gurion did advocate forequal wages and jobs for the Arabs in Israel. To me, that is still not enough.

Just then Ma’ayan comes up to us.

“Who was David Ben-Gurion, saba (grandfather)? Why was he such an important person?”

“Ahhh…well, he was one of the founders of the state of Israel,” my father tells her in a story-telling voice. “He was very brave to persuade the world that the country needed to exist at a time when Jews were not being treated well around the world. He was also one of Israel’s first Prime Ministers. What did you learn on the iPad?”

I walk ahead of them, holding hands with Jessie.

Jerusalem

As soon as we arrive in Jerusalem, I am suffused with memories. I had forgotten how all the neighborhoods are built into the sides of the hills and how pretty it is when the light shines on the pink Jerusalem stone. “This neighborhood is where I lived when I was twelve!” I exclaim to Jessie and Ma’ayan, pointing out the window.

Our Airbnb is downtown, on a street filled with construction, only two blocks away from the cobblestone streets lined with shops where I used to go after school with my friends to buy pizza with green olives.

The Old City

At 9:00 the next morning, we meet our guide, Benayah, outside the Jaffa Gate for a tour of the Old City. He is a middle-aged man with a weathered face wearing a kovah tembel (peaked sun hat) and a backpack. “Shalom,” he says, making an effort to engage Ma’ayan by stooping down and shaking her hand.

After walking down many steps, we stand outside the city walls and he explains how the city was built layer on top of layer, using an old picture book and his own drawings as illustration. I am awed by this tangible evidence of history. My daughter seems less impressed. She is concentrating on climbing up and down the steps, and I’m not sure she is even listening.

While he lectures about Jewish history in the time of King David, I notice the Arab neighborhood across from the Old City. I am surprised to see that there is a blue and white Israeli flag flying from one of the balconies.

“What is this neighborhood?” I ask, pointing.

“That is Silwan. They are hostile to Israel.”

“Why? How come there is an Israeli flag there?” He does not know.

I am skeptical about his perspective, especially since he stated support for the Trump administration’s move of their embassy to Jerusalem.

Later, I look up information about the history of Silwan on my phone and discover it is a predominantly Palestinian village with about 40 Jewish families living there. In 1948, it came under Jordanian rule and then fell under Israeli rule after the Six Day War in 1967. In 1980, it was made part of the Jewish Jerusalem, a move that has been called illegal under International Law. Evidence for the existence of holy sites, such as the tombs of prominent officials from Judean times and other archaeological ruins believed to be within the old boundaries of the City of David, have incentivized Orthodox Jewish organizations to make claims to the land. They even gained government support for buying some properties belonging to Palestinians and evicting at least one Palestinian family in the area.

Today, Benayah shows us old coins and castles. We tour some ruins, then he takes us underneath the Old City and through the Hezekia tunnels, an old sewage system. Some parts are so narrow that the walls brush my arms. I start to sweat with claustrophobia, longing to escape. Benayah reminds me of the Israeli teachers I had at Jewish Day School in Canada, the ones who passionately drew maps of Israel on the blackboard and told us a one-sided version of Jewish history and Zionism.

We finally exit near the Wailing Wall, the outer wall of the temple built in the time of King Solomon.

“This is the Kotel,” says Benayah. “I will leave you here.”

This used to be a place I too found sacred. When I was a child living in Jerusalem, I even wrote about the “ancient call to prayer in Hebrew and Arabic” in my diary. The women’s section in front of the Kotel is much narrower than the men’s, crowded with people swaying in prayer. I used to believe that if I placed a slip of paper in the cracks of the wall, God would read it or listen to my prayers.

“Mummy, can I write a note to Zaida Zaida?” Ma’ayan wants to communicate with her great -grandfather who died last year. I take a slip of paper and a pencil, and she writes a private message, not showing me what it says.

As we approach the Wall to place her note in one of the cracks, we see hundreds of other slips of paper. She asks, “Mummy, what happens to all the notes?” I think, cynically, that they probably get swept up at night or rained on.

“God and Zaida Zaida read it.” She nods and hops over to an archway to look at a stray cat. I hope this is an acceptable answer.