Reclaiming Europe’s Jewish Past and Present

Living in Europe for the past few months, I’ve been struck by the similarities between traditional Jewish and European dishes. I was vaguely aware of these similarities, but seeing them in reality is different. For example, the many Christmas markets in Munich (where I’ve been living since September) sold a potato dish called Kartoffelpuffer or Reibekuchen—essentially the German version of a latke.

As I dug a bit more into the similarities I found, I discovered a fascinating story centered on a Jewish woman from Vienna, a city that, before the Holocaust, had a thriving Jewish population.

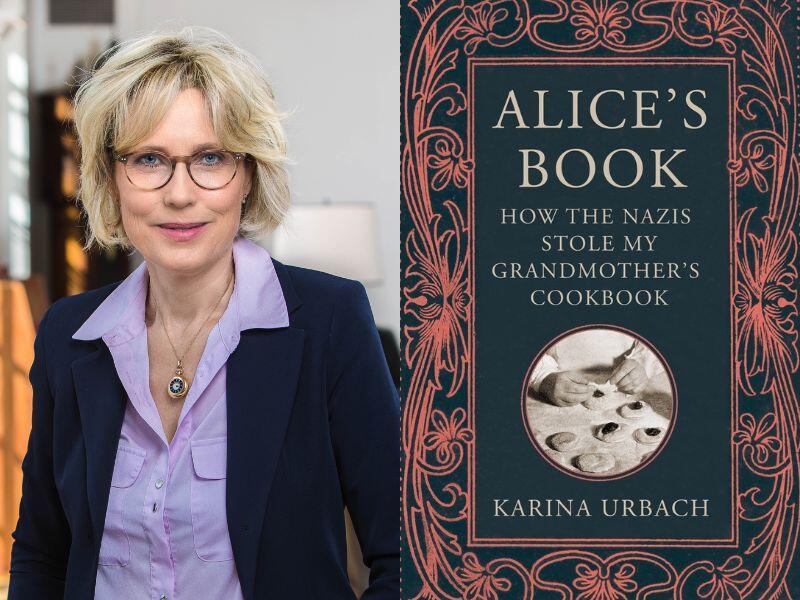

In 2020, the German historian Karina Urbach published a book titled, Das Buch Alice: Wie die Nazis das Kochbuch meiner Großmutter raubten. Two years later, the book was published in its English version: Alice’s Book: How the Nazis Stole My Grandmother’s Cookbook. The book details the life of Urbach’s grandmother, Alice, a well-known chef in Vienna before World War II, who found similar renown in the United States in the decades after the war.

As Karina explains in the book, Alice spent the first part of her adult life as a housewife and mother in Vienna. After her husband’s death in 1920, Alice began her career as a chef, mainly as a way to earn an income. She published her cookbook, So kocht man in Wien! (That’s How They Cook in Vienna!) in 1935. Due to increasing antisemitism, Alice left Vienna for England in 1938. Her older son, Otto, had already immigrated to the US as a young man. Her younger son, Karl, also tried to leave, but was arrested and sent to Dachau, a concentration camp. For unknown reasons, he was released in 1939 and immigrated to the US. After the war ended, Alice also moved to the US.

Alice’s career is fascinating all on its own. She taught cooking to people such as the Prince of Liechtenstein, ran her own culinary school, and appeared on cooking shows in the United States But Alice’s cookbook makes up the heart of her granddaughter Karina’s book, for good reason. After Alice left Vienna, her book was republished under the same title, but not under her name. The Nazi regime instead attributed the book to a man named Ralph Rösch—a man who, as Karina discovered through extensive research, didn’t exist.

Alice wasn’t the only victim of this act of plagiarism. Karina describes in her book how the Nazi German regime repeatedly stole books from Jewish authors, framing them as the product of Aryan intellectualism. In the case of Alice’s book, several recipes were also Aryanized, with any associations to Jewish culture removed. For example, the names of recipes like “Rothschild sponge” or “Jaffa torte” were Germanized, and some explicitly Jewish recipes were omitted entirely.

Despite Alice’s efforts, she was never able to have her book republished under her name. Karina’s detailed history is the first acknowledgement of the extent to which Nazi Germany obscured the works of Jewish authors like Alice. It was only in 2020 that the German publisher acknowledged Alice’s original authorship, and only as a result of Karina’s book.

Alice’s work and life story are intertwined with Jewish history, and highlight how integrated Jews were in Viennese life before the war. Although there were Jewish influences in her cooking, Alice wasn’t known for her “Jewish recipes.” Rather, she was particularly good at making popular and fashionable European foods, including pastries and delicacies such as petit fours and ham pastries. She developed a number of finger foods that were popular at bridge matches because they could be eaten with one hand. The popularity of her cookbook, which was a bestseller before World War II began, reflects how ingrained her cooking was in Viennese culture, even when published under a different author’s name.

Jewish Viennese food blogger Nino Shaya Weiss points out that, even during a period when Viennese Jews were assimilating, their culture was both Viennese and Jewish. For example, a 1913 cookbook by Jewish couple Olga and Adolf Heiss titled Viennese Cooking included recipes that were coded in a way that a Jewish reader would know they were meant for Passover and other Jewish holidays. The Jewish references in Alice’s book were more explicitly Jewish, which was a problem for the Nazi party; Weiss notes that several recipes from the book, such as Krautfleckerln (cabbages and noodles), were suppressed in the Aryanized version of the book because they were “too Jewish”.

Weiss also highlights the life of Sigmund Freud, whose Jewish identity is often obscured in modern biographies, much like the history of other Viennese Jews. In a fascinating twist, Alice Urbach’s story crosses paths with Freud’s, if only tangentially. While still teaching culinary arts in Vienna, Alice had Sigmund Freud’s daughter, Anna Freud, as one of her students. The two women encountered each other again later in life: after Alice emigrated to England in 1938, she found work caring for girls who had moved there through the Kindertransport, a series of efforts to rescue Jewish children from Nazi-controlled Europe and bring them to Great Britain. Alice sought out Anna’s expertise (like her father, Anna was a psychoanalyst) in addressing the post-traumatic stress some of her students were dealing with.

Alice’s story also exemplifies many Jewish women’s experiences in the early twentieth century. She lived the life of a struggling housewife and mother, using her domestic skills to provide for her family. Alice survived in England, unable to help her son, who was still stuck in Germany. She was incredibly resilient in the face of hardship.

Karina Urbach’s book is an important reclamation of her family’s past, as well as the history of Jewish communities in pre-Holocaust Europe. Weiss’ blog offers a similar reclamation, in the form of foods like Krautfleckerln that have become so much a part of their modern Austrian and German cultures that their Jewish past was nearly erased.

These works show the world that Jews were here, are still here, and will continue to be a vital part of European life and culture.