Queer History and Stone Butch Blues

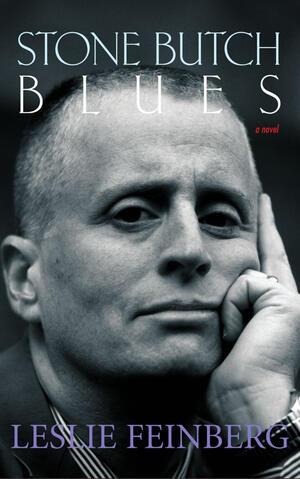

Two years ago to the month, I read Stone Butch Blues for the first time. Leslie Feinberg had made previous appearances in my life, distant traces of hir legacy filtering through references in other books and news of hir death months prior, but it wasn’t until May/June 2015 that I finally sank into Feinberg’s oeuvre and felt the force of hir most famous book.

At that time, I was at a precipitous moment in my own life. I had recently moved to Oakland, a bastion of radical queerdom, and started a job at Keshet. These life changes signaled both an entry into the Jewish world and the beginning of my transition into a more realized genderqueer identity; around that time, I started asking to be referred to with they/them/their pronouns.

As I awakened to the possibilities of a life and community that reflected my internal self, I sought out texts that would illuminate this core. From Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room to Preciado’s Testo Junkie, I immersed myself in queer reality. On this journey, I came to Stone Butch Blues and found tucked between its pages another prism of queer experience. Through a single character’s narrative, I explored myriad refractions of the queer self in the world.

Even though Stone Butch Blues recounts a culture from decades before that has since faded, reemerged, and shifted, reading it still felt like a homecoming. As someone whose community is comprised largely of queer women and other marginalized genders, I felt a kinship with the identities and communities Feinberg portrays. As a young person waking up to the power of activism, I saw myself in Feinberg’s protagonist, Jess Goldberg, and her burgeoning awareness of the power of politics and organizing. In Jess’ drifting from the gender assigned to her, I saw a parallel with my own gender squirming away from what I’d expected.

Stone Butch Blues is not an easy text to pin down. It’s too facile to assume it chronicles Feinberg’s own life; despite the obvious parallels, ze insisted upon its fictiveness. And despite its focus on one main character, Stone Butch Blues still meanders subject-wise, delving into many of the biggest incidents and eras in the decades it moves through.

As a marginalized group, we are discouraged from seeing ourselves in history. We are taught only the hegemonic course and forced to erase ourselves.

Pre-Stonewall LGBTQ consciousness is rare beyond trivia. Stonewall is often white- and cis-washed. Even the more recent AIDS epidemic remains shadowy in broader cultural consciousness. The mainstreaming of certain parts of our community has buried others—just as we see the lesbian liberation movement overtake butch/femme bar culture in Stone Butch Blues.

Therefore, we must look at Stone Butch Blues as queer history. Despite the insistence of its subtitle “A Novel,” Stone Butch Blues takes on the work of memorializing past iterations of queer life.

That’s why Stone Butch Blues remains an essential text, radically reminding us of the variation and mutability within the LGBTQ populace. The breadth of our experiences and struggles have too often been brushed over and simplified. We’ve not solely been gays and lesbians fighting for marriage rights, we’ve also been he-shes and drag queens—warriors at the holy fringes of gender and sexuality—fighting back to stay alive and to be safe if not seen.

Stone Butch Blues is my history and it’s not. There are many aspects that resonate with me, and so many that don’t and never will.

I’m not a “he-she,” a butch, or transmasculine. I’m a genderqueer/nonbinary person. I was assigned male at birth. I go by “them/them/their” pronouns, but I am often perceived as a man and sometimes afforded the privileges and safeties that passing can bring. It’s complicated for me to comment on a book told through the eyes of a stone butch from the lesbian culture of the past. If I’d been alive at the time, maybe I would have been a fierce femme/drag queen like Peaches or a gentle creative transwoman like Ruth. However, despite having femme stars in the constellation of my gender identity, I don’t know that I could ever have inhabited a more resolutely feminine space. On top of that, the narrative never focuses on that transfemininity in the same way it does on Jess and the lesbian experience. As such, the book isn’t really for me, a nonbinary, gender nonconforming person.

And yet, I do see myself in some of Jess’ experiences such as after she gives up hormones and passing as a man, when she becomes more of a “gender outlaw.” The confusion the world feels toward her and the turmoil it incites within her. The ways we must cage our own selves in order to save ourselves.

I see myself in a scene where Jess, working at the bindery in New York City, hears co-workers approaching and conceals herself between vending machines, only to hear co-workers talking about their discomfort in her presence and the otherness they cannot name but perceive nonetheless.

Stone Butch Blues shows that the world as many of us experience it: fraught with pitfalls impossible to navigate, uncertain if a moment could unleash vitriol or violence. We secure ourselves as much as we can, pass when we must, silence our truths if necessary.

And of course, there’s another aspect of Stone Butch Blues that speaks to me and my experience: Feinberg’s portrayal of community space, and hir illustration of the fragile power of space—timeless in its sheltering.

What I think of the bars of Stone Butch Blues and their denizens—femmes like Millie and Edna, butches like Al and Edwin, queens like Georgetta and Peaches—I think of my own bars and the beloveds I frequent them with.

There’s a calming sanctity in our queer spaces. The ones we create for ourselves. We let facades fall, reveling in the freedom we’ve found in like-souled family. It’s beautiful. Unfortunately, although we don’t have the same bar raids and forced closures depicted in Stone Butch Blues, our spaces are still vulnerable.

Think of the closing of the Lexington Club in the San Francisco Mission. Even more drastically, think of the massacre at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando. Holdouts of safe and free queer expression are still being erased, invaded, and assaulted. Our spaces and ultimately our bodies are still on the line.

Stone Butch Blues doesn’t just recall the past, but actively speaks to our present—as all good literature does. What it lacks in subtlety, it makes up for in earnestness. Even through its atmosphere of hardship and even desolation—appropriate for a book with “blues” in the title—it retains a bleak hope, the core to queer self-preservation.

As we wait and work for a time when all spaces are safe, when I don’t have to weigh my need to fully express myself against my safety, when pundits and leaders don’t think our lives are expendable, you can find me in at a bar. I’ll be under the arm of a butch, hands clasped with a femme, laughing with abandon at something a genderqueer friend just said and for a moment, I will feel no fear––just as Jess dreamed about in Stone Butch Blues.

Note: I use “she/her/hers” for Jess Goldberg as that is how Feinberg most often refers to her, and though Jess journeys through passing-manhood for a time and uses “he” pronouns for safety, she ultimately identifies herself as a woman toward the end of the book. It would feel objectionable to assign pronouns to the character that had not been assigned by Leslie Feinberg.

Jess is everything I want to be and a lot of things I'm terrified of being. Im middle class, transmasc and I didn't come out as bisexual until gay marriage was legal in my country but somehow Jess made me feel so seen that I cried. I can't explain it, it's like meeting a parent for the first time and realizing that parts of you were passed down for generations even though that makes no sense. all my little fears and wants and hopes were in that book. I learned what kind of man I wanted to be from a butch and I won't forget it.

Stone Butch Blues was an immensely important book for me as well as an AFAB non-binary person. Thank you for highlighting Leslie's legacy and hir books' ability to describe the internal world of queer people.