Powerful Wives, Then and Now

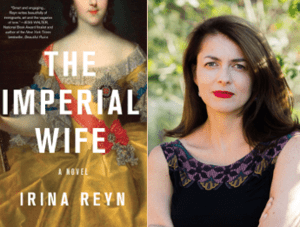

I did not set out to write a historical or timely novel but I do think The Imperial Wife proved to be both. Ironically, it was only by looking back at eighteenth-century Russia, during the time of the fascinating ruler Catherine the Great, that I was able to think more deeply about the challenges facing contemporary women in America.

When I first started conceiving of my novel, it was 2008 and Hillary Clinton was running against Barack Obama for the Democratic presidential nomination. I saw a public, vocal, discomfort with a woman in power emerge in our culture. (Of course, I could not have foreseen how this discomfort would be so much more apparent in our recent election.) I wanted to explore the notion of powerful women not only in politics but also in a domestic context. Do we still have a problem when the woman holds the more powerful position in a marriage? Is our culture uncomfortable with a wife who is the professionally successful spouse, the more capable one, the chief breadwinner? Have we come far enough to no longer see this dynamic as shameful or taboo? More importantly, I wondered: how does the wife feel about occupying this role?

In order to explore this dynamic, I dug deep into the life of Catherine the Great. Personally, I’ve always been a little bit obsessed with Catherine, just as my friends were obsessed with the Tudors. What drew me to her (other than her being a Russian ruler, a country from which I emigrated) was that she was an Empress with absolutely no dynastic right to rule. Here was this strong woman who ruled a huge nation for over twenty years at a dangerous time in history but, unlike Queen Elizabeth or even Mary Queen of Scots, she had no birthright to the throne. A relatively low level princess, Catherine’s parents did not have high hopes for her future success because she was not beautiful. Ignored, Catherine spent her time reading and thinking, turning what was originally a flaw into a virtue. When she married an Empress’s nephew, there was absolutely no reason for Catherine to be an Empress in her own right. But in memoirs (if you believe her retelling of her early life), she understood that she was far more capable of running a country than her husband was; she had a talent for rule that he completely lacked. Peter III was volatile, childish, an alcoholic with no political acumen. He was also incapable of producing any kind of heir, so Catherine procured lovers to provide some fake heirs and solidify her position. Soon after he took the throne, she overthrew him in a coup, her supporters had him killed, and she ruled the country for over twenty years! Only her death gave her son the throne. That’s some serious chutzpah.

By comparison, my twenty-first century protagonist, Tanya Kagan, is all too aware of how women in power must play down their strength to succeed in today’s world. A head of the lucrative Russian Art department at a major auction house, she is a Russian Jewish immigrant whose parents expect her to play the role of the docile wife—they are proud that she is so successful at her job but worried this will make her unattractive to a husband who has not had the same professional success. Most of her clients are Russian oligarchs and Tanya knows that to be successful, she must fit their feminine ideal: dainty, intelligent but never overbearing. And finally, Tanya is all too painfully aware that her husband feels insecure next to her accomplishments. When he leaves her, she wonders what she did to drive him away.

Many readers have found it ironic that Catherine, living in the eighteenth century is the gutsier woman. She takes what she thinks she deserves while Tanya is cautious, getting what she wants by tiptoeing and playing the roles others expect of her. Readers have found this remarkable and that was my intent. I hoped that readers would wonder: Why isn’t Catherine’s story more typical today? Why is her ambition and rise to power still such an aberration, three hundred years later?

The women in my book, and in the world, must navigate so many identities: Jewish, Russian (in my case), mother, wife, employee, daughter. We, as women, are all too aware that we are always shuffling these identities inside of us; we are unconsciously (or consciously) putting forth the one that will be most accommodating to an outside observer. In her recent book, How Women Decide, cognitive scientist Therese Huston wrote, “I’ve found that when a man faces a hard decision, he only has to think about making a judgment but when a woman faces a hard decision, she has to think about making a judgment and navigate being judged.” While I did not read this book while writing The Imperial Wife, I wanted to bring a similar understanding to Tanya’s story. At the auction house where she works, she is coded as “Russian,” so she can sell art to Russians, she is coded as “Jewish” to her Russian clients, her parents want desperately for her to be “American,” and to the JCC, where she volunteers, she is a part of the young, Russian-Jewish community of professionals they are working to energize. In reality, Tanya feels like none of these identities but knows she needs to assume those personas in order to give everybody what they need from her. In the midst of all this juggling, what does she want? And how does her strength and competence impede her in her personal life? I wanted to examine a life where something that should be a virtue comes to feel like a major flaw.

Historical fiction matters today more than ever. Historical fiction, like science fiction, is an important genre because it allows us to draw explicit connections between past and present and future. Anytime there is collision of time periods in fiction, we are forced to ask ourselves the following questions: what has changed? What has remained the same? Are we in a better place? Where are we headed? Whether the writer intends this contrast, setting our worlds in different times forces that confrontation for the reader. This very inversion through time and space created by an explicit connection to the past reminds us that we may not have come quite as far as we think. And it should, I hope, spur us to action.

Read The Imperial Wife, JWA’s book of the month for February, and learn more about JWA’s Book Club here.