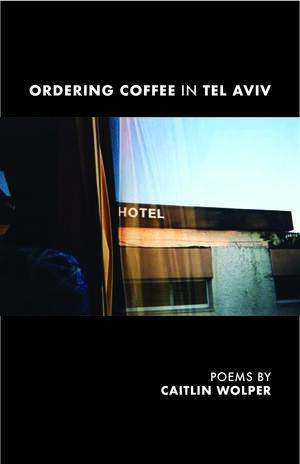

Ordering Coffee in Tel Aviv

Caitlin Wolper’s first poetry collection, Ordering Coffee in Tel Aviv, is a powerful account of a young Jewish woman’s first trip to Israel. Spanning place (Tel Aviv, the Dead Sea, Manhattan), time, and perspective, this chapbook takes the reader on an at times painful journey of self-discovery. Wolper powerfully grapples with themes of gender, identity, and “the leash of Israel’s legacy.”

The following is Wolper’s exclusive reflection for JWA about her inspiration and creative process for two selected poems.

POET, PARATROOPER, AND PRISONER OF WAR

Did you recite your own poetry

when your parachute

split open? You fell first

as a plan, but no man

could have guessed

the fall to imprisonment:

your second descent.

When you faced the firing squad,

you refused to wear a blindfold.

Hannah Senesh, have I known you?

If I could ever deserve it,

I’d go by my second name, Chaya,

the one that sounds like yours.

I’ve pictured your cell,

two strides in length

where cross-legged, you cut out letters

to form words, flashed mirror-light

to send signals to the other prisoners,

and sang all the while, song stretched

between bars. You sketched David’s stars

in the dust of the floor,

painted a sky beneath your feet.

Did you look down their barrels?

Each day I age closer to your end,

stride toward your 22.

As you wrote in a poem before the execution,

life is a fleeting question mark:

only so many strides across—

The die were cast, I lost.

When I visited Mount Herzl in Jerusalem, we stopped before a set of graves: One belonged to Hannah Senesh. Our tour guide played “Eli, Eli”—a poem-turned-song she wrote—over his cellphone speaker as we stood. He told us she’d been a poet and a paratrooper who died in her early twenties. I was twenty myself. Something about her story stuck with me, though I knew little. I jotted down her name on the bus later so, when home, I could learn more.

When I read that she was killed by firing squad and refused to wear a blindfold—looking right into the enemy’s eyes during execution—I wanted to know her expression. I couldn’t fathom such tenacity. This poem is both a glimpse at who Hannah Senesh may have been and a personal excoriation: I challenged myself to be as mature and brave as her. It’s also an attempt to honor Senesh as a prisoner who clung so readily to faith, “sketching stars” in the dust on her cell floor and singing with her cell mates. Hope until the end—another concept I struggle with.

I recognized in Hannah a ferocious courage I am unable to match, and wondered how I could even grasp at it. In this poem, I examine the parallels between us as poets and young Jewish women and where I fall short of her legacy, all while being in awe of it.

WOMEN IN THE DEAD SEA

Am I proven sinful

when the Dead Sea burns

the sex between my legs?

The delicate pH of woman!

Our bodies, always shamed

for personal pleasure: salt stings

before we’ve time to float.

Our buoyancy will cost us.

After Eve’s fall, all women

must burn like this, sear

when united with nature.

After a minute, floating above current,

the sensation dissipates.

Still, the memory of heat flares

each time we reenter the waves.

People are warned not to shave in the days before they enter the Dead Sea because the salt stings even the smallest cuts. However, no one warned me that your vagina burns when you enter: the salt throws your pH balance into disarray. My first reaction to this sensation was that something was wrong with my body, either that I’d become aware of some latent disease, or I wasn’t made correctly. It made me wonder if I belonged there. And by the time I’d pondered that, the uncomfortable sting had vanished; I’d acclimated to the water.

Here I was, in a holy spot, the lowest elevation on Earth, and I had to pay for it with pain. I thought immediately of Eve, the pain of childbirth that was bestowed upon her after the original sin in the Garden of Eden. Now, still, in the modern world, why do women have to suffer pain to experience something ethereal, something holy?

I wondered, as a woman, am I inherently sinful? And how do we overcome this Biblical precedent that we have earned suffering, a concept I—and anyone with a feminist perspective—absolutely abhor? Before I could enjoy the Dead Sea and delight in it with my fellow travelers, I had to be reminded that I was a woman. I stung from what felt like a wound, and it ruined a beautiful moment. All I wanted was to experience natural beauty, a wonder of the world, but first I had to pay a physical price.

I love putting milk (not cream) in my coffee!

When my children were young and attended a Secular Jewish Sunday School, I learned about Hannah Senesh along with them. Many years later I went to Israel and visited Senesh's gravesite. I found it to be a very emotional experience. I admire Caitlin Wolper's talent in expressing so well what she and I felt.