More than “Galentine's Day”: Recognizing Female Friendships

Recently, a few of my clergywomen friends dropped by a congregational Shabbat dinner, and we spent the latter half of the evening catching up while people finished their meal. Some members of my community didn’t know how to process the presence of these women at my table, and a few expressed resentment that my attention was divided.

As I responded to this, I wondered if the reactions would have been different had the people dropping in been “family” (my colleagues assure me that any person who vies for the clergyperson’s attention is met with scrutiny). Living on my own, hundreds of miles from my family of origin, these women are the only people outside of my congregation with whom I regularly share Shabbat.

We check in with each other on an almost-daily basis. We’ve been each other’s rides for surgical procedures. We expect to be in each other’s homes on holidays. They too have families who live several hundred miles away, and, while not all of us are single, each of us lives alone. We rely on each other as a support network. It would be diminishing to refer to these women merely as “friends.”

Or perhaps we are not giving the word “friend” its full weight.

Around this time of year, the celebration of female friendship is treated as a feminist (or snarky) alternative to Valentine’s Day, and is addressed in an equally shallow, commercialized way. One example of this is “Galentine’s Day,” an invention of the fictional Leslie Knope on Parks and Recreation that has taken root in the real world.

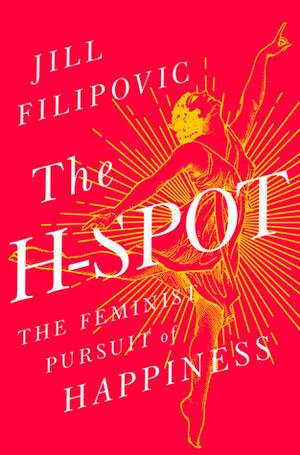

But, as Jill Filipovic suggests in The H-Spot: The Feminist Pursuit of Happiness, female friendship is no consolation prize. The H-Spot addresses how society might benefit from the creation of public policies directed towards the ideal of women’s happiness: by providing them with means to earn a living wage, seek out healthy relationships, plan their families and care for them. And one of the strongest predictors of happiness for both men and women, Filipovic writes, is having “deep tie” relationships.

Filipovic points to studies that show that friendships can have a beneficial impact on one’s health, and, for many women in the United States, “fill the gaps of a punctured social safety net.” Women are shown to have biological impulses to help one another in times of crisis, an impulse UCLA researchers call “tend and befriend” as opposed to “fight or flight.” Throughout the history of the women’s movement, it was often through female friendships that women discovered a common cause with one another, and began to organize and advocate on behalf of themselves and their families. These relationships can be particularly important for minority women and LGBTQ women, who draw strength from friendships with women who share their experiences.

For Filipovic and her friends, friendship was the one constant during the tumultuous early years of adulthood. Friends served not only as a source of support, but as sounding-boards as Filipovic and her peers contemplated the women they wanted to become, the experiences they were having in work and life, and the kind of partners they ultimately wanted to share their lives with (if they married). Filipovic writes:

“Women today have more varied, dynamic, and outward-looking lives than ever before, and as marriage and even serious romantic partnerships are also delayed, female friendships take on a new role: they tell the truth that no one person can be everything for another, that our lives are richer when we get what we crave from a variety of sources.”

When I first arrived in town, a few clergywomen in the area reached out to befriend me. Though we had little in common aside from ordination—we weren’t even from the same faith—we had a laundry list of common experiences and connected instantly. When it comes to the unique experience of being a female rabbi, I rely on an online forum for support and best practices. In a profession—and a location—that can be isolating, these connections help me to feel less alone.

For all of the benefits of friendship, Filipovic points out that our society fails to recognize the importance of relationships apart from marriage or nuclear families. In some states, limits are placed on how many unrelated people can live in one home (particularly women, as a vestige of anti-brothel laws), as well as on who can make medical decisions on a person’s behalf, limiting people’s choices about whom they identify as “family.” Moreover, Filipovic argues, we might offer more financial support to secular institutions that—just like religious institutions that already enjoy tax breaks—provide essential social networks to people who desperately need them.

As we approach Galentine’s Day (and its romantic counterpart), let’s remember that female friendship deserves more recognition than a midday mimosa. It deserves the type of legitimacy bestowed on romantic partnerships and nuclear families, because, for many of us, our friends are our support network and our sounding board, our lifeline and (part of) our family.

And to my local crew, Megan, Leigh, Heather, and Liz, thank you for filling my table.

Marianne Lieberman

I have enjoyed women as friends all my life. At age ten I formed a club with four school-friends based on a book called "Bibi and her friends" back in Vienna,Austria. I have always shared my life with women. Especially to find balance to our male relationships.

I am very happy to say that yesterday my husband and I celebrated the 55th anniversary of our marriage. But I can also say I don't know how I'd make it throughh this life without my women friends.