MLK and the Civil Rights Movement: Doing it Justice

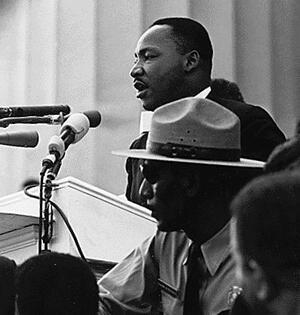

When I say "Martin Luther King, Jr." what comes to mind? I would bet you see him standing at the Lincoln Memorial, overlooking a sea of people on the Washington Mall, and hear the evocative words of his "I have a dream" speech. I understand why King's speech at the March on Washington in August 1963 has come to represent his life's work and his legacy, and why the moment is celebrated as the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

But as memorable as that day was, we don't do justice to King's life if that is all we remember. Today I'm thinking about his last campaign, the Poor People's Campaign, planned for the spring of 1968 and finished posthumously. In this campaign, King focused on economic justice for blacks and whites, demanding an "economic bill of rights" and a $30 billion anti-poverty package for jobs, housing, and income. In May 1968, one month after King's assassination, demonstrators arrived for a two-week protest in Washington and thousands of poor people, traveling in caravans from all around the country, set up a shantytown known as "Resurrection City." As uplifting as the 1963 March on Washington was, this March was equally disheartening. It rained every day, turning Resurrection City into a flooded, muddy mess. After a month, the shantytown was shut down; an "economic bill of rights" has yet to be passed.

The Poor People's Campaign is not an inspiring, "feel good" story. But it needs to be remembered, nevertheless, for what it reminds us about the radicalism of King's later years and the unfulfilled challenge that still hangs in the air.

I feel similarly about the story of Jews and the Civil Rights Movement -- a story that we tend to remember selectively. It's a story we're both celebrating and complicating in JWA's new online educational project, Living the Legacy. Sure, it's true that Jews were disproportionately represented among civil rights activists, comprising an approximated one-half to two-thirds of white activists -- an astounding percentage given our small representation in the population. That figure suggests an important story about Jewish commitment to social justice, Jewish identification with African Americans, Jewish response to our history of oppression.

But those numbers are not the whole story, and to focus on them is to miss part of the picture. We also need to talk about how some Jews in the South were hesitant to risk their precarious social position to stand up for civil rights for African Americans. Take, for example, this letter from the Hebrew Union Congregation in Greenville, MS, to the Reform Movement's Union of American Hebrew Congregations, rebuking them for inviting Martin Luther King, Jr. to speak at the Union's Biennial Convention in 1963.

Or consider the resentment some Jews in Northern cities felt toward their black neighbors as neighborhoods shifted, as attorney and civil rights activist Will Maslow described succinctly in a confidential report to the American Jewish Congress in 1960:

The more important cause for this new fear and hostility is the movement of Negroes into what were formerly Jewish neighborhoods... The inevitable deterioration of the public schools, the overcrowding in the streets, the increase in "mugging," all bring about a panic withdrawal, either flight to the suburbs or the more expensive all-white East Side or a determined effort to insulate oneself by sending children to private schools and keeping them off the streets. This new fear and consequent hostility is sensed by Jewish leaders in a new opposition to public school integration or fair housing practice acts and a vast indifference to Federal civil rights legislation relating to suffrage.

These kinds of urban civil rights issues, rooted in issues of economic justice, remain salient and unresolved today. In our enthusiasm to celebrate the Jewish activists of the Civil Rights Movement, we should not elide these less flattering examples of Jewish response to racial issues, for we need to learn from them, too.

In his final speech, given in Memphis on April 3, 1968, the night before he died, King drew on the biblical image of Moses on the mountain. He said that he had "been to the mountaintop" and seen the Promised Land. He assured his audience that, though he might not get there with them, "We, as a people, will get to the Promised Land."

We're still not there. But we owe it to King, and to all his fellow civil rights activists to keep striving, to learn from the past -- from successes and failures -- and to cast our eyes forward. We celebrate King today, not only for what he accomplished but also for the work he left for us to do. We honor his memory best by taking it on.