Midrash for a New Generation

I remember when I first learned about midrash, the practice of "filling in the gaps," in biblical texts, in Hebrew school. We were reading the story of Cain and Abel, and our teacher pointed out that during the fight that precedes Cain’s fratricide, the Torah does not tell us what the brothers fought about.

“But,” the teacher said, “many people have imagined what might have happened.” Suddenly, biblical literature was infinitely expanded—there was not only the Bible, but the stories that explained, explored, and questioned the Bible. These investigations of the holy stories were not only acceptable to create, but canonized in their own right. As a child with an interest in writing and an overactive, character-driven imagination, I found myself in the rare position of looking forward to doing my Hebrew school homework that week and writing a midrash of my own.

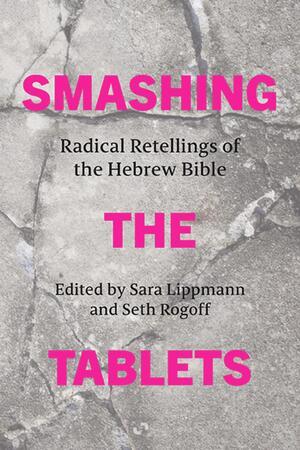

A similar sentiment is palpable within the pages of Smashing the Tablets: Radical Retellings of the Hebrew Bible, a new anthology of short stories, personal essays, poems, and more, edited by Sara Lippmann and Seth Rogoff. It would be easy—perhaps too easy—to categorize the contents of this anthology as midrash. The foundational impulse is the same; as Lippman and Rogoff write in their introduction, “Arguably the most significant characteristic of biblical narrative is the existence of narrative gaps.” It reminds me of the oft-quoted Joan Didion adage, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” In order to make sense of the Torah's stories, we tell more stories.

But whereas midrashim typically maintain the context of the Torah's stories, putting words into the mouths of the characters as they appear on the page, Smashing the Tablets sheds the confines of ancient times. The writing in Smashing the Tablets is emblematic of that titular metaphor, recontextualizing biblical stories into bodies, landscapes, and cultures that feel closer to the writer’s experience.

The titular reference goes beyond the conjured image of the writers breaking narrative forms, and, as Lippmann and Rogoff explain, has biblical significance, too. Many of us know the Exodus story of Moses smashing the tablets after receiving them on Mount Sinai and being greeted upon his return by the Israelites worshipping a golden calf. But Lippmann and Rogoff point out an interesting nuance I had never noticed —the first set of tablets (the ones Moses destroyed) were inscribed upon directly by God, whereas the second set (which survived) were dictated to Moses by God. As Lippmann and Rogoff put it, “The human finger has overwritten the divine finger.” This event is central to the anthology’s thesis, that we have permission to “smash” biblical texts to create stories that feel relevant, meaningful, and perhaps more immediate than the original stories, while still speaking to Jewish values.

This thesis is exemplified by two of my favorite stories in the collection, “A Little East of Jordan” by Moriel Rothman-Zecher and “The Job Book” by Steve Almond. Rothman-Zecher’s story is four electric pages, reimagining Jacob wrestling with the angel as protagonist Jake’s night in a gay club, where he encounters a nameless, angelic man who dances with him all night. While the context is, of course, radically different, the resolution is the same: in the morning, the protagonist feels reborn with new purpose due to this physical encounter, and as Rothman-Zecher writes, re-enters the world feeling “not afraid or ashamed.” He has passed the angel’s test. “I can feel that most of the time, you’re sure you need to do, to achieve something, to struggle,” the angel tells Jake, “but tonight, you can just be, there’s nothing left for you to do. You’ve made it. The fight is over for tonight.” Rothman-Zecher saw the common themes between Jacob’s story and many queer narratives—shame, yearning, and a desire for fulfillment —but instead of merely discussing these similarities, he placed them in the hearts and minds of characters more recognizable to a modern queer audience, in turn expanding the reader’s understanding of the original text.

In “The Job Book,” Almond reimagines the Book of Job in a wealthy college sorority. As an undergraduate, the protagonist, nicknamed “Yinzie,” develops an obsession with the story’s Job stand-in, Dina, the sorority’s popular social chair with a God complex. After graduating, Dina’s wealth and social prowess only increase as she becomes the head of a multi-level marketing scheme. Then, two tragedies strike in quick succession: the reality of the scheme is exposed and her husband and children die in a plane crash. The protagonist reconnects with a broken, faithless version of Dina. This story intrigued me because (with apologies to my childhood rabbis) I was unfamiliar with the Book of Job before reading Almond’s story, beyond the broad strokes. Given the story’s playful title, I guessed that Dina was a stand-in for Job, and after reading a summary of the biblical source material, I see the parallel between their respective character arcs: how it is easier to be faithful when everything is going your way, and the real test happens when your privilege is lost. Almond presents this quandary to the reader in a more accessible style than the dense biblical text. Through this secular text, I was able to understand a part of the Bible I had never studied before.

That being said, I often found myself having to google summaries of Bible stories as I read Smashing the Tablets to deepen my understanding of the stories within. There is no guide or cheat sheet in the anthology, and not every piece makes it clear which biblical narrative it is referencing. Similarly, the book jumps from fiction to non-fiction to poetry to more experimental storytelling and back again, which sometimes makes for a jarring reading experience. But Lippmann and Rogoff have compiled a truly excellent roster of writers whose work stands on its own, whether the reader is familiar with the source inspiration or not. There’s something in Smashing the Tablets for everyone, whether you’re a Hebrew school dropout dipping your toe back into Jewish commentary or a biblical scholar looking for new ways of seeing familiar parables. The writing in this anthology is wonderfully inventive and indeed as radical as the title suggests, reclaiming ancient narratives for a modern audience.