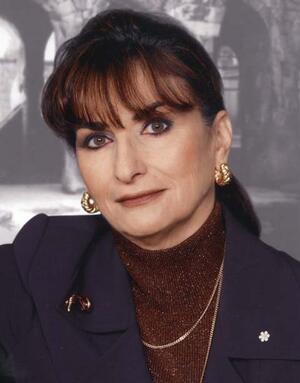

Judy Feld Carr: Rescuing Thousands from Syria

"Judy Feld Carr... arose when it was ‘still night’ and woke up the world to the plight of our brethren in Syria," announced the leaders of the Syrian-Jewish community in honoring the Canadian woman who single-handedly engineered the escape of more than 3,500 Jews from persecution in their homeland.

Institution: Judy Feld Carr.

As the news is flooded with reports of refugees fleeing Syria, we have found ourselves remembering a very different Syrian refugee crisis: the mass exodus of persecuted Jews from that country from the 1970s through 2001. I recently spoke with Judy Feld Carr, who arranged 3,228 of those rescues by forging passports, bribing officials, and arranging for individuals and families to be smuggled across the border. What’s amazing about her story is that Judy wasn’t a Special Forces commando or a human rights lawyer; she had no background in this type of work.

Despite that, she built a communications network, learned to bribe officials, paid for fake passports, found reliable smugglers who could take people across the border by night. “I used to have the children’s mouths covered with tape so they wouldn’t cry. And they had no food. One diaper. One change of clothes. No pictures, no memories, nothing on my escape routes. Every time, it was devastating worry. But each one of them made it, because I was so careful. So careful.”

How did a musicologist from Canada end up saving thousands of lives?

Judy’s incredible story began in 1972, when she read a newspaper article describing how a group of Jews tried to flee Syria only to stumble into a minefield and die while border guards watched. Outraged, Judy and her husband, Dr. Ronald Feld, wanted to help, but in those pre-internet days, with no Syrian free press, how could you even figure out whom to contact, let alone get a message to them?

After weeks of trying to place a call to anyone in the Syrian Jewish community, Judy managed to get through, but little did she know that the woman she had reached was an informer for the secret police. Luckily, the woman was away, or Judy’s attempt to help would have been over before it started. The woman’s husband hurriedly gave Judy contact details for the local rabbi and the Jewish school in Damascus. “He was so scared, I thought he was going to have a heart attack on the phone. And the line went dead.” She then sent a telegram to the rabbi, who answered with a request for books. Remembering something she had once read, Judy decided to send a hidden message in the shipment of books with a code used by Jews during the Spanish Inquisition. “I figured, Jews in Syria, some of them came during the Inquisition.” The rabbi’s next telegram used the right countersign. They were in business.

Word got around Toronto that Judy was raising money to send more books to Jews in Syria. A Syrian woman in the community told Judy she was determined to visit her brother in Aleppo before he died of cancer, and asked what she could do for Judy while she was there. The woman was with her family less than a day before the secret police captured her for interrogation, grilling her on her connection to Judy and brandishing the telegrams Judy had been sending to the local rabbi. The woman insisted she knew nothing, and was finally released. But when she returned to Canada, she had a letter for Judy signed by three rabbis, which she had smuggled out in her underwear. It read: “Remember, we are all Jews. Our children are your children. You must take our children out of Syria.” Judy recalled being overcome: “It was like a letter out of the Shoah. I just cried. I don’t know how to do this.”

Now the woman begged Judy to help rescue her dying brother. Judy pointed out that at the time, “Syria was a steel trap. There is no communication outside of the country for the Jewish community. They’re living in only three cities, and we later found out that they can’t travel further than three kilometers from their homes without special permission from the secret police.” The brother was in Aleppo. The embassy was in Beirut; it might as well have been on the moon. Judy pleaded with the Canadian ambassador to visit the local rabbi at a school in Damascus and give him the travel papers to smuggle to the brother in Aleppo. “I made the only mistake I ever made in all the years of rescue. I told him to go to the school at 2:30. I thought the secret police left the school at 2:00. They actually stayed until 3:00. But that day, God was looking down on us: the agent of the secret police was sick with the flu.” The rabbi got the papers.

Judy had an ambulance waiting at the airport for the brother’s arrival in Canada. “When he came into the hospital, I had a Jewish doctor who had been in the Canadian army during WWII. He told me, ‘I haven’t seen a body like that since Auschwitz.’ They had beaten him brutally every time one of his children escaped. His back was covered in scars. And his arms, my God. And this was a man who was dying of cancer of the bladder and kidneys.”

Before he died, he told Judy, “I have one last thing to ask you. I have a daughter. She’s pretty. She’s single. She’s nineteen years old. I’m worried that without me, there will be no one to protect her. She’s either going to go into a forced marriage or be raped by Syrian army officials. Can you get her out?”

Judy rescued the girl. And then the girl’s sister. Then more families. Even people in prison.

Through all this, she avoided any hint of publicity. “I’ve had four threats on my life. Physical threats. This isn’t a joke.” But it wasn’t just about the risk to her personally; she had to make sure the corrupt Syrian officials kept taking bribes and had no reason to save face by cracking down on her underground railroad. “No one in Canada knew I was doing this; no one in Europe knew I was doing this. Until the Mossad came on the scene and told me to stay home and wash windows and take care of my kids.” She ignored them and kept working, and eventually they began supporting her efforts.

“I was working on an escape the day of my father’s funeral,” she remembered. “I had to go from bank to bank—I needed a lot of money for this escape—and then a courier was going to pick this up and take it to Israel and then Turkey. My father’s funeral was delayed by two hours ‘for an emergency.’ What could be a greater emergency than a funeral? But I had to. There was a mother and four or five daughters, and they told her if she tried to escape, they would gouge out her eyes. I never told my mother the reason, but I did tell the rabbi afterwards, because I had to tell somebody. He nearly fell off his chair.”

Then, a brief window of opportunity: in a show of good faith as part of peace talks between Israel and Syria in the 1990s, the Syrian government lifted most travel restrictions on Jews. There was a mad scramble to rescue all the remaining Jews from Syria before that window closed, and while some were able to get out on their own, or with the help of other organizations, the fund Judy had created paid ransoms for 623 people who couldn’t afford the fees on their own. In all, over a period of 28 years, she managed to rescue more than 3,200 Jews.

The extreme care she took to avoid publicity meant that most Syrian Jews never met “Miss Judy,” who arranged their rescue. But some still seek her out. At the Jewish Women’s Archive, we are reminded of her incredible story every time we get periodic messages from refugees trying to reach her and thank her.

Several, in gratitude, have named their daughter Judy.

Touching story. Amazing woman.

Amazing. Thanks for sharing

What a courageous wonderful woman.thank you for telling this story.