Interview with "Harbor from the Holocaust" Co-Producer, Iris Samson

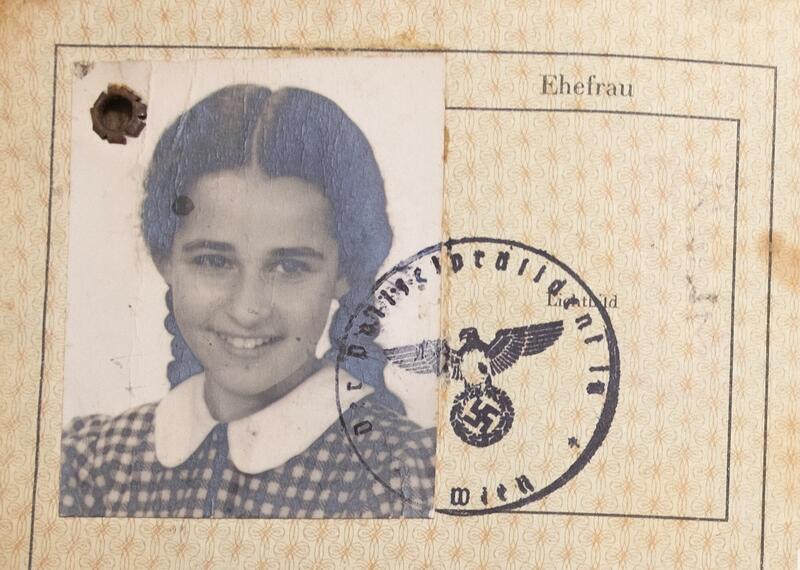

For three years, Iris Samson has been working on a documentary. Through name changes and edits, the film has always stayed true to its mission: to tell, faithfully and thoroughly, the story of the “Shanghailander” Jews who fled Nazi persecution and landed in China. Following Kristallnacht, a loud and ringing warning that it was time to get out, Jews who had lined up outside of consulates from around the world found a saving grace: the consul general from China in Vienna, Ho Feng Shan. Holding on to visas and little else, thousands of Jews set sail for a place many had never heard of. Shanghai, a home to other Jewish communities already, would take in thousands of Jewish refugees and leave them with experiences and memories that stay with them to this day.

Harbor from the Holocaust airs Tuesday, September 8 on PBS.

As the production associate and archival research assistant for the documentary, I spoke to Samson about this project and her long career in media.

Tell me a little bit about your journey in the world of documentary filmmaking.

I began as a print journalist, working for almost 25 years in the field before taking classes in documentary filmmaking. I enjoyed it and thought of it as a continuation, in some form, of my journalistic career. Though there were some major differences, including learning to tell a story through visuals rather than words, it was just as satisfying.

You’ve worked with JFilm (Jewish Film Festival in Pittsburgh) for a while! Can you tell me about that part of your life?

Many years ago I was approached to get involved with JFilm. At first I resisted—I was working full time and didn’t think I’d have much to contribute. But it’s a wonderful organization with not only entertaining programs, but also an incredible educational component that brings teenagers from all walks of life to a theater to see a film with a Holocaust theme, or a theme related to teaching humanity. I’ve seen it change young people’s lives, and it gave me the push to remain with the organization. From there, the program grew and grew—and I was tapped to be the chairman for many years. I’ve probably been chair off and on for almost ten years (but am not presently, though I’m a chair of the Robinson Short Film Competition). I like that we provide the opportunity to nurture young filmmakers, too, through the Robinson Competition.

What is the hardest part of producing a documentary?

The hardest part of producing a documentary is probably getting started. There’s so much involved—from determining the subject matter, to tracking down interviewees, to procuring funding and your crew, and establishing a workable schedule. The first phone call is always the hardest, but once that first interview is scheduled, you get on a roll.

Tell me a little bit about Harbor from the Holocaust and how this project got started.

Harbor from the Holocaust was the brainchild of Darryl Ford Williams, the Vice President of Production at WQED-TV. She was inspired by a traveling exhibit that featured the stories of Jews who had survived the Holocaust by escaping to Shanghai. Darryl contacted me and asked me to join the production as a researcher. It was bashert, fated, because my husband’s three uncles and an aunt survived the Shoah by leaving for Shanghai. In the early stages, we had to get funding just to proceed. That came from the National Endowment for the Humanities. From there, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting liked the project and gave us the bulk of the monies, which also included some small Jewish foundations participating as well. We hired our director and one of my jobs was to find the subjects to be interviewed. The entire process took almost three years!

The more we talked about this story, we realized we actually had a lot of connections to it! My grandfather had relatives who went to Shanghai, and my parents’ neighbor in San Francisco had been there, also. Why do you think the story is still unknown to a lot of Jews?

I think there’s a few reasons people don’t know the story. It happened in China, before the Revolution. Jews started leaving in 1947 and 1948, before the Communist Party took over in 1949, and it wasn’t part of their story. It’s only been in the last few years that the Chinese government publicized it, the way that the story of Jews in Europe was publicized. But that’s not the main reason. We know a lot of Holocaust stories because they’re tragic and mind-boggling. The numbers are hard to wrap your head around. Those stories are compelling and enormous; they get you. This is a positive story! Of course there was suffering. People died. There was hunger. They gave up everything to get there. But they survived! And you don’t hear too many stories of positive things that happened during the Holocaust.

What’s the most important thing you learned working on this project?

Although I was a Jewish Studies minor, and I’ve worked in Jewish journalism for over two decades, and I’ve produced dozens of Holocaust stories for local broadcast, I didn’t really know the story of the Shanghai Jews. It’s an amazing story—there was an [Iraqi] community already there in the 1840s; the Russian Jews came in the early 1900s, and then the German, Austrian, Polish, and some other European Jews came fleeing Hitler in the 1930s. But in addition to the historical perspective and knowledge that I gained, I had the opportunity to interact with survivors who showed extreme courage and resilience. That’s probably the best part.

In the film, the strength of Jewish women and Jewish mothers during a traumatic experience is mentioned frequently. How do you think this relates to Jewish history?

Jewish women were integral to the Shanghai story. First, Jewish mothers, wives and daughters fled to a completely foreign experience and held their lives and families together—and in fact, helped them flourish. But I believe that’s usually the case; women are strong and capable, and we seem to find the way to cope with the day to day incidents—and even the traumas—that shape us. For Shanghai, two of the major figures who helped the refugees were women. One, Lucie Hartwich, was the principal of a school that provided normalcy and a haven for hundreds of Jewish children. She ruled with a “gloved” iron fist and made sure that the children received an education that would take them to all the corners of the earth. Laura Margolis, who came to Shanghai through the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, set up soup kitchens and a hospital, negotiated with the occupying Japanese army to help the Jewish community survive, and helped organize relief efforts. As one of our interviewees said with great emotion, “She was a saint.”

What are some lessons you hope people take from the story of the Shanghailanders?

Perhaps the most important lesson from Harbor is that we should open our arms to refugees, to people fleeing persecution whenever possible. In Shanghai, it was almost as much the story of happenstance—only a few individuals actively tried to send Jews to Shanghai to escape the Nazis, but it was fortunate happenstance that Shanghai existed. To know that 18 to 20,000 Jews survived in a completely unexpected place is the story of fate, of karma. We may not understand how it happened, but it is hopeful.

We got to work in a woman-majority producing team on this project! Do you think that makes a difference?

It was an amazing experience to work in a woman-majority producing team. The ability to be empathetic, to put people at ease, to “listen”—these skills were all integral to making a successful production (and we tend to associate them with women). We were also a completely professional team that meshed well together. I’ve worked on many local documentaries and perhaps because of my age—I’m 61—and my relatively newness to the field, I tend to defer to others. Here, I felt comfortable taking the helm and providing leadership. It was so refreshing!

watched this on PBS. assume same movie. very well done and timely. thank you

suzanne tishkoff