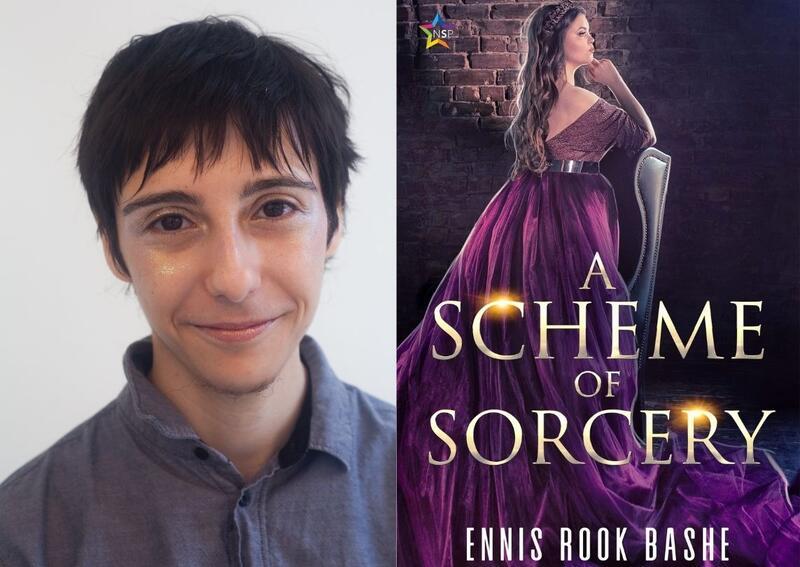

Interview with Disabled, Non-Binary, Jewish Poet and Novelist Ennis Bashe

Ennis Bashe (they/them) is a Jewish, disabled, non-binary poet and novelist. Their new book is A Scheme of Sorcery. JWA recently talked to Ennis about why fantasy fiction is the perfect genre for writing about disability, how their different identities intersect, and what they want every disabled and able-bodied person to know.

JWA: What is Ehler-Danlos syndrome?

EB: Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is a connective tissue disorder, which means that the stuff that holds the body together, collagen, isn’t formed correctly and doesn’t do its job. I once saw somebody describe it on Twitter as being held together with Post-it notes and everybody else is held together with duct tape. In my case, it affects my joints, blood vessels, and organs. I’m very lucky in that I can digest food and live independently, which many people in the community aren’t able to do.

JWA: Can you talk about some of the ways of living with a rare disease has affected you?

EB: Although Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is a lifelong genetic condition, it only started hitting me hard during college. At that point in my life, I thought I was going to go into theater and travel a lot. My long-term plans involved backpacking across Europe, like my mother had done at my age, and learning more about choreography and dance. When I woke up one day and my knees hurt so badly that I couldn’t make it to the cafeteria, things changed. At first, I figured I had a temporary infection that could be cleared up with a few rounds of antibiotics, but getting more accurate medical information made me realize that wasn’t the case. As a result, my priorities in life changed. I spent more time writing and volunteering, which led me to the career paths that I have now, and settled down with my cat instead of being a nomad. I admit to feeling wistful sometimes, but on the whole I’m really happy with how my life has worked out. When I first got sick and had no way to manage my symptoms, I didn’t think I’d be able to live a productive life. I’m very grateful for how everything has worked out.

JWA: When the disease started affecting your mobility, you turned to various forms of self-expression, including poetry and fiction. Can you talk a bit about your work and its overarching themes?

EB: I’ve always enjoyed words and I started publishing my writing in high school. When I saw female characters given the short end of the stick in popular media, I realized I could give them a better ending and share my writing with other people who also felt cheated by the mainstream narrative. That’s been one of my main goals as a creator—to provide recognition to people whose lives and stories haven’t historically been viewed positively by majority groups. I want to make people who don’t often get to experience characters like them feel seen.

JWA: Why is fantasy fiction a particularly good outlet to express yourself, and how do you use it to convey important messages about disability and identity?

EB: I think fantasy fiction is a great vehicle for social awareness because it allows people to look at issues from a new perspective. For example, even though most kids don’t know how to approach somebody who looks different, everybody loves Nemo from Finding Nemo and his “lucky fin.” Fiction allows people to realize that others are just like them in many of the ways that matter.

JWA: You’re also pursuing a degree in social work. What are you hoping to achieve once you graduate?

EB: Although there are so many amazing jobs out there, so I don’t have it narrowed down, I would love to work with groups. I think being a good group therapist is a lot like being a good writer. It’s all about showing people that what they’re going through is normal and that they aren’t alone.

JWA: You’re the child of a rabbi. How does your upbringing and Jewish identity inspire your writing and activism?

EB: I credit my family with helping me develop my mind. I was encouraged to think deeply about societal problems at a young age. My parents supported me starting my own nonprofit in childhood, a natural outgrowth of the book of ethical dilemmas we would discuss every night around the dinner table. I’ve grown up learning how to analyze a text at the deepest possible level and not take even a single piece of punctuation for granted.

JWA: More generally, can you talk about ways your different identities (Jewish, disabled, queer, writer) intersect?

EB: I feel like having so many different identities has given me the skill of being able to explain myself and my perspective. For example, I often meet people in the queer community who don’t know about disability, or people in the writing community who’ve never met a Jew. I also get the chance to relate to so many amazing people and writers who I have things in common with, and I am really blessed in that way.

JWA: What are some things you want able-bodied people to understand about people with physical limitations?

EB: The most important thing I want to tell healthy people is, “Please don’t panic when you learn about our symptoms.” Every so often, I casually mention something that’s normal for me, like, “Hey, I black out if I stand up too fast, so give me a few minutes” or “Be right back, I dislocated my shoulder and need to put it back in.” The shocked reactions that I tend to get from the abled are completely out of proportion. I’m not stressed out, so why are they panicking? Now I have to use the energy that I need to take care of myself to reassure the crowd of strangers.

Panicking isn’t helpful, but you know what is? Asking the disabled people in your life how you can better accommodate them. Many disabled people have been disbelieved or even abandoned in the past when we disclosed what we needed to make something accessible. Let’s say you’re hosting a party—be proactive about making sure everyone can get into the building and have a seat at the table.

The third thing I want everyone to know is that it’s the “disabled” community. Not the “special needs” community, not the “differently abled” community, not the “diff-ability” or “differently empowered” community, or whatever silly euphemism someone’s invented recently.

Which brings me to my fourth point: “disabled” isn’t a bad word. No one is going to tar and feather you for using it.

Finally, please don’t be weird about seeing a disabled person in the street. I hope one day I can go outside with my cane without a complete stranger asking inappropriate questions.

JWA: What advice would you give to other people who have disabilities or limitations?

EB: Many people who are disabled think they’re inadequate because of society being judgmental. But the people who are truly limited are those who judge others based on things they can’t control, or who make assumptions about what someone can achieve in life based on a disability. Bigotry is the most limiting trait a person can have.

What a poignant, beautiful and edifying interview. I will share it broadly. Thank you so much!

You're inspiring! Thanks for telling it straight, like it is. Your parents must be extremely proud!