I Visited Six European Jewish Communities to Explore My Own Identity

When I decided to study abroad in Stockholm starting in January 2022, I realized that in addition to the personal growth from living on my own for the first time, I also had an opportunity for spiritual growth, the chance to explore what Judaism meant to me in a new and unfamiliar context.

I identify as a Reform Jew, which is quite common in the US. But in Europe, where it’s less common, I struggled to find my place in the Jewish community. I felt simultaneously too religious and not religious enough, and it made me realize how different European Jewish culture was from American Jewish culture.

Wanting to understand these differences, I proposed a travel fellowship project to my college that involved exploring Jewish communities in different European countries. My travels took me to six different communities, each presenting me with unique perspectives and challenges as I connected with community members.

It’s hard to do justice to all of my experiences in a single piece, so I’ll focus on three cities I visited—Venice, Riga, and Berlin—that raised questions for me about what it means to be Jewish, to be Jewish in Europe, and to acknowledge and move forward from the horrors of the Holocaust.

Venice

Shortly into my time exploring the Venetian Jewish Quarter, a glass shop caught my eye. “David’s Glass,” the sign read. And under that? A glass Rabbi. A glass Torah. A glass mezuzah. A glass evil eye. A glass Star of David. My heart soared. I’d passed many kitschy Murano glass shops, and as an admirer of glass, I’d always stopped to look. But glass crosses inevitably lined the display cases at most stores, and I never felt compelled to buy anything. Seeing David’s glass shop, I felt excited—a Jew who loved glass and could make these amazing works of art. How exciting!

I decided to strike up a conversation with David, the shop’s owner. He explained that his sister was a glassblower in Murano, and that she sent all her works to him to sell in his glass shop across the street from the synagogue. Historically, Venetian Jews were kept out of the glass industry; guilds were formed as gatekeepers to the industry, and few Jews ever participated, relegated instead to being bankers and traders. This is ironic, considering that the work of Jewish glassmakers was admired and emulated as early as 687 CE. Despite Jews introducing glass to Venice, they were quickly excluded.

David’s sister’s departure from this norm opened an opportunity for a glass shop in the city in which all items were crafted by Jews. (I later learned that David’s was the only Jewish glass shop in Venice.) David said his customers were a mix of locals looking to buy nice gifts for the Jewish holidays and tourists looking for souvenirs. He remarked that in Italy, there were very few Jews, and much of Jewish culture had been washed away with the second world war. In the post-war era, a time when Italy struggled financially, many Jews felt afraid to be too successful, lest they become targets again.

David’s assessment of the Jewish population in Italy made me think about assimilation: Was it our duty as Jews to stay true to our cultural heritage no matter where we were? Or was it worthwhile to blend in for safety and adopt a new culture, even if that meant giving up some of our own?

I see both sides. When standing out as Jewish means becoming a target for others and being in physical danger, I understand the benefits of blending in. I don’t wear a Star of David necklace for this reason. While I am proud of my Jewish identity and enjoy engaging in interfaith dialogues about it, I also fear that people who know nothing about me other than that I am a petite Jewish woman might take that as an invitation for violence.

At the same time, I recognize the importance of speaking to community members and being visibly Jewish and present in the community. When with friends, I often bring up Judaism, whether to say something tastes like challah, reminds me of Purim, or that some situation warrants a Yiddish saying. In these casual moments of recognition, where people have gotten to know me as a Jew (among the many other identities I hold), I have had people ask me questions about Judaism, ranging from “What is kosher?” to “Is it scary being Jewish in America?” These opportunities for dialogue are crucial: Stereotypes often form when people make incorrect assumptions about others and don’t see the humanity in them. By engaging in these conversations with me, my non-Jewish peers come to see Jews as less mysterious, more similar to them.

My time in Italy made me think about one of the tensions of being Jewish, at least for me—wanting to blend in on the one hand, but also wanting to stand out and engage with the wider community.

Riga

The Jewish community in my next stop—Riga, Latvia—felt very different from Venice. Whereas the Jewish community in Venice, though small, seemed cheerful and homey, the Rigan Jewish community stood out for all that has been lost.

The ghetto of Riga has been remarkably well-preserved. Crumbling but original buildings and walls surround a portion of the town. A replica train car—like one that would’ve passed through only 80 years ago, taking Jews to concentration camps—stands in the center of the ghetto, a memorial to those who were transported, never to return. Mirrors line the inside of the car, prompting visitors to reflect on the lives lost in the Holocaust, and how many of the visitors today would have faced a similar fate if in the same place 80 years prior.

Of the 30,000 Rigan Jews imprisoned in the ghetto, 25,000 were taken and shot dead by SS officers in the Rumbula Forest over the course of two nights at the end of November and beginning of December 1941. Having emptied the ghetto, the Nazis proceeded to deport another 20,000 Jews from across Europe to the Rigan ghetto and concentration camp. The cycle of murder continued.

After saying the Mourner’s Kaddish to remember those lost in the Holocaust and placing a stone atop the memorial plaque, in keeping with Jewish tradition, I spoke with the young Jewish man who worked at the historical center about his experience of modern Jewish life in Riga. He described the community as small, close-knit, and primarily drawing people who had settled there on their way to Israel—first temporarily and then for good. Like most Eastern European countries, Riga’s modern Jewish community was vastly diminished from what it once had been—from about 50,000 to only a few thousand today.

One original house from the ghetto that survived both the war and the subsequent Soviet occupation was divided in two: a memorial with models of Riga’s 32 destroyed synagogues occupied the lower floor and an upper floor replicated how Jewish worshippers were crammed into the building. The images of the destroyed synagogues lingered with me as I explored the rest of the city. Gaps haunted the spaces between buildings—some from the destroyed synagogues and others from buildings that never were rebuilt after the Soviet occupation.

Overall, my time in Riga left me with a profound sense of loss. While other European cities had rebuilt after the war, Riga felt very much suspended in time. The Jewish community, too, felt frozen, even as it grimly moved forward from the tragic history of the city. It was hard, the man from the ghetto explained, to move forward so close to so much loss.

The sense of loss that pervaded Riga made me think of my own experiences with grief. Having lost two people dear to me—a mentor to Covid-19, and my father to cancer—I have been confronted by the painful reality of loss. It can be hard, in the face of such pain, to simply plant a flower and make a garden. I myself still feel the weeds of loss from time to time. And I see how in a larger community, where everyone moves at a different pace, has a different story, and is faced with different physical reminders of such tragedy, regrowth becomes even more difficult.

Berlin

In Berlin, I hoped to answer the question of how Jewish communities rebuild. Though my days in Berlin were sunny, warm, and beautiful, I felt coldness in my heart as I compared the city’s Jewish community today to what it used to be. In 1933, 160,000 Jews lived in Berlin. Today, that number is 30,000. Still, many of Berlin’s Jews today are newly arrived immigrants, which signals regrowth and renewal, despite the city’s tragic history.

While in Berlin, I thought a lot about the issue of forgiveness. Jewish tradition emphasizes seeing the good in people, believing that people can grow and change, and granting second chances. One of our holiest days, Yom Kippur, is centered on the idea of asking for forgiveness and granting it to others.

Yet, I was struck by how angry I felt about what the German people at the time had let happen to my people. At a flea market, Shabbat candles and menorahs were placed carelessly with cutlery and kitchen goods. My frustration rose when I saw this. How could people not understand the sanctity of these religious objects? How could they be sold in good conscience at a flea market, when they deserved to be given to a museum for proper care?

I spoke with Roman, a Jew who had moved from Ukraine to Berlin, where he had lived for 40 years. I asked about his perception of the Berlin Jewish community. He noted that it was largely divided into two groups: Newer Jewish immigrants from the collapsed Soviet Union who settled there (instead of continuing on to Israel as originally planned) and an older but smaller community who, by some stroke of luck, survived the Holocaust. As different as these two groups were, they both agreed on one key point: avoid standing out too much within the city. The New Synagogue of Berlin, after all, had been a point of contention between local Germans who felt it ostentatious and local Jews who took pride in the beautiful architecture, when it was built in the mid-nineteenth century.

When I asked Roman why he chose to live in Berlin if it meant he had to assimilate, he smiled wryly, “In the war, you don’t run to avoid the next bomb,” he said. “You go to the buildings that were just blown up. Bombs don’t hit the same spot twice, yeah? Unless you’re really unlucky.”

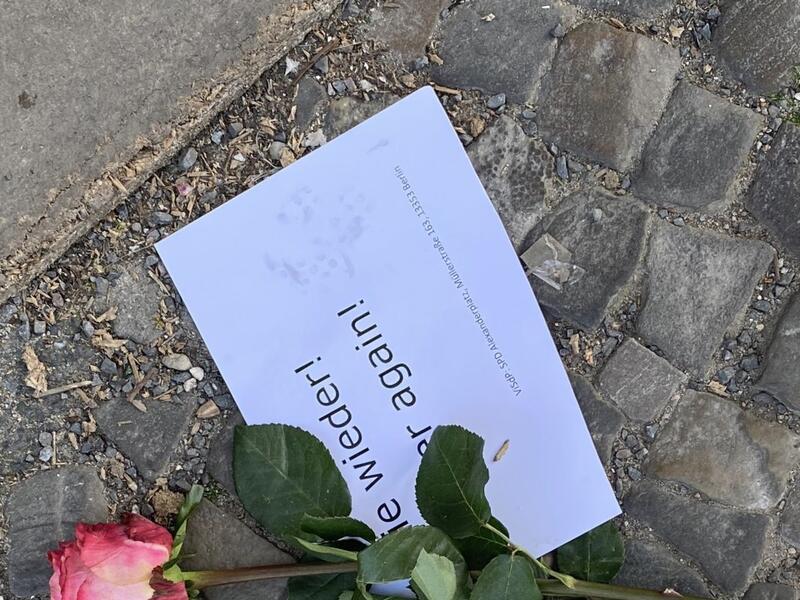

The logic was chilling but made sense to me. Jews in Berlin had seen the worst that could happen. So had the Germans who lived there. Because of the atrocities that had happened here, decimating the Jewish community, it was considered fertile ground for regrowth—albeit in a more subtle way. Walking around parts of Berlin, it was easy to forget that such a dark history had happened here. Even with the brass plaques in the ground reminding passersby of the murdered Jews, Berlin had grass growing amidst any remaining rubble piles, flowers blossoming amidst the treetops, and an artsy hipster vibe.

My travels didn’t give me all the answers, but they did help me clarify my role in finding them. Thanks to my experiences in these different countries, I feel more comfortable and at peace with my decision to assimilate into American culture, while also holding space for dialogue about my Jewish identity. I feel more comfortable reconciling loss and regrowth. And I feel even more strongly than before how important it is for me to engage in dialogue with people living different religious experiences. The highlight of each city was the personal connections I was able to cultivate, regardless of whether our opinions aligned. Those are the connections and memories I will cherish as I seek to find my place in a Jewish community as an adult.