Grabbing Back the Pussy: An Interview with Jayna Zweiman on the Pussy Hat Movement

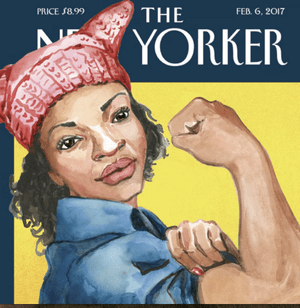

In less than six months, pink pussy hats have taken over America. If you’ve never seen one, you’ve probably been living under a rock since the election (not that I could blame you). These hats—knitted or crocheted from pink yarn, with two iconic points—are a staple of today’s marches and protests, worn by hundreds of thousands of women to protest a president whose blatant misogyny would be laughable if it weren’t so terrifying.

But where did these hats come from? It turns out that they’re the creation of three Los Angeles women: Jayna Zweiman, Krista Suh, and Kat Coyle. The Jewish Women’s Archive talked to Zweiman to get the story.

How did you come up with the idea for the pussy hat?

I’ve been recovering from a concussion for a couple years now. So much of the healing process is really isolating, and so I roped in my friend Krista [Suh] to learn how to crochet with me. We discovered this incredible community at the Little Knittery, a knitting store.

We went there on November 10, after the election, to be with our knitting community. It’s predominately women there, and it seemed like the right place to process what had happened. By then, the Women’s March had been announced, and Krista was going to go to D.C. I had this huge deep desire to be there—but how could that happen, given my injury?

Krista realized it was going to be cold and that she would need a hat. Then she thought, what if other people wear hats too? And so she got in touch with our knitting instructor, Kat Coyle, and asked for a pattern for a hat. Then we realized that if I couldn’t be at the march, there were likely many people like me. The person who makes each hat can also be represented at the march, even if they’re not there in person.

And so we teamed up: we made a PDF with a pattern and a description of the project, and then shared it.

How did that sharing work? How did this idea catch on so quickly?

Kat is part of the knitting world, and she let people know who have important blogs. We set up on social media on all fronts, including Ravelry (the knitters’ site), and really utilized those. We reached out to yarn stores across the country, the kind that might have classes and that host communities. We contacted them and got them on board. That was really important in terms of trying to create spaces where women could talk about politics in a community atmosphere.

But we also tapped into people who had never been knitters before. The idea was that anyone could participate, even people who couldn’t attend marches for medical, financial or other reasons. You could be a knitter, a crocheter, a marcher, or none of that—you could just spread the word. Whatever skill you have, whatever you can give, you can be part of the project. We started to get picked up by more and more blogs. We asked people who were knitting to tell their local newspapers. Then the Huffington Post picked us up, and then national news. It’s incredible to be in the middle of all this. It's amazing.

How did your own background and career fit in with this project?

Almost everything I’ve worked on has ended up in this project. I worked on Bill Clinton’s second campaign and inauguration, and worked at the White House at the National Economic Council when I was in college. I also worked at start-ups, as an urbanist and game designer for Mobile Urban Scavenger Hunt. I’ve worked for various architects, taught architecture, and worked for design builders in Los Angeles. I’m now working on my own practice. This project really brings in an understanding of architecture, how networks and spaces and people get brought together, as well as my art background. In some ways, this is a huge participatory art installation.

Why do you think these hats caught on so quickly?

A lot of people were really shocked by the election results. What we heard was that a lot of people were really depressed and had no idea what to do with themselves. This was something you could physically do that was positive, it was kind, and it was a way to connect and use your voice. When a knitter or a crocheter makes a hat, she can include a note about which women’s rights issue is important to her. She then gives her hat to a marcher directly, to one of these local yarn stores, or sends it to our collection site in DC. That way, if you’re in the middle of Kansas, you can still connect with people on the basis of women’s rights, in a really positive and personal way. I think that’s really a beautiful thing, in this time of social media when we just forward articles. That feels very not real. Actually, making a hat is one of the most real things you can do.

This may be an impossible question to answer, but do you have a sense of how many hats have been made?

We haven’t run visuals on each of the marches to figure it out! We know, at the very least, hundreds and hundreds of thousands. I’ve heard a million, but we don’t have solid data to back that up.

Let’s talk symbolism. What is the hat meant to represent?

Krista asked Kat for something really distinctive, and I asked for something easy to make. The idea of having a form that was recognizable, but not typical, was really a strong part of this. So, Kat designed the prototype for the hat. I asked her what it was called, and she paused, then said, “The pussy power hat.

From there it was very clear that this was the Pussy Hat Project. It was a play on words: pussy cat, pussy hat. It was also a reference to the Hollywood Access moment, with Trump’s pussy grab comment. That was really a moment in the election that both sides of the aisle came together and said, this is not okay. So this was an opportunity to really think about how the word pussy is about the feminine in a really derogatory way. If you call a girl a pussy, or a boy a pussy, it’s really not used in a positive way. We wanted to change the way that word is used, and look at the feminine as something that’s powerful and strong. And have room for conversation about words like this, and what it means to be a woman. It’s a really tricky word. It wasn’t a word that I ever used before this project. Now I personally find it to be really positive and joyful and about people coming together.

One criticism we’ve seen of the Pussy Hat Project is that it excludes trans women who don’t have the same genitalia as cis women. What’s your take on that?

I strongly support the trans community. I have a lot of respect for the trans community. I think it’s really important to listen to what they have to say. It makes me sad because so much of the project is about trying to include as many as possible, and the idea that the most marginalized group of women feels marginalized, is sad.

The word pussy is meant to be derogatory towards everyone, towards everyone’s feminine qualities. That’s more of what I was thinking about when I made this project: feminine qualities, not necessarily the specific genitalia.

Going forward, I think it’s important to pay attention to the most marginalized of women’s groups. A lot of cisgender women are also very uncomfortable with the word pussy—but I think it’s important to raise awareness. Women’s bodies are being legislated, whether they’re trans or cisgender, and reproductive rights are very much on the chopping block. I think a reference to the pussy and the womb is not necessarily inappropriate within the terms of the Women’s March. But that being said, we definitely welcome the trans community. I really think that we all just have to listen to each other. We have a lot in common and a lot to learn from each other. There is no such thing as perfection, and the more we try to support each other the further we’re going to get.

Did your Jewish upbringing influence your decision to pursue this project?

I would say absolutely. I’m a very fortunate person. I have a wonderful husband, I come from a wonderful family, I’ve had the opportunities of education, and still it’s been incredibly difficult after my accident. I’ve been thinking about how can I make this better for someone else who’s going through the same thing. And I think at the heart of the pussy hat, it’s my tikkun olam to the max project. How can we make the world a little bit better?

I’m the granddaughter of four immigrants, and when I think about the Holocaust, I think, would I be one of those people who was sneaking people through the border? One of those people who was standing up and protesting? That’s so much a part of my Jewish upbringing: understanding where my family came from, and so much of the luck that we had, that I even exist. I’m the product of the Jewish-American dream, and trying to extend that to other people is my responsibility.