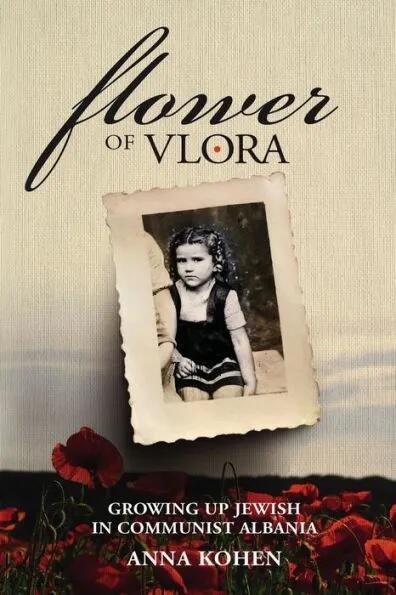

"Flower of Vlora": A Memoir of Romaniote Jewish Experience

From the moment I found out I was not the only Albanian Jew, I devoured all content related to us. Anna Kohen’s memoir, Flower of Vlora, was no exception.

Kohen hails from one of the oldest diasporic Jewish communities in the world. Her community of Romaniote Jews have lived in what became Albania, Macedonia, Greece, and Turkey for two and a half thousand years, outside borders and beyond nationalist conceptualizations of identity. They have outlived dozens of polities and quite a few empires headed by men ranging from Alexander the Great to Adolf Hitler. They have lived along the shores of the Aegean and Adriatic long enough to see the first and second temples fall.

Flower of Vlora charts Kohen’s life from her childhood in Vlora, Albania to her dentist ambitions in New York City; from her unexpected and happy marriage to her commitment to helping Albanian refugees. Kohen’s memoir pulls my heart between a past I wish I could have seen and a present I am grateful to be living in. It also challenged me.

Common in women’s writing is the conflation of humility with self-effacement. However, Kohen subverts this trope in her work. Her honesty about the difficulty of achieving her career goals as a dentist inspired me to demand that women around me ask for what we are worth. Kohen does not minimize her achievements or labor. We must know that stating what we bring to the table is not bragging. It opens the door for anyone who is being treated unfairly to do the same.

It is Kohen’s matter-of-fact voice that sets the tone of her memoir. It is familiar, no-nonsense, honest, and brusque. She discusses the volatile and unpredictable outbursts of her late father honestly and with compassion early on in her memoir. He sometimes unexpectedly flips tables or flys into a rage, but Kohen presents her own experience without shame. Intergenerational trauma and abuse in Balkan families are issues I know well. Seeing this dynamic represented in literature by someone from my background made me feel less alone, and more like I was capable of surviving it.

My heart soared when I read about her college relationship with a boy. It’s not an arranged marriage (as is often the norm)—she truly follows her heart and her ambition even when that means she no longer wants to be in that relationship. Her liberal and independent nature stands in contrast to my own Macedonian Albanian family’s religious conservatism, which often frowns on women dating. It is a welcome alternative to point to when I imagine women in my generation with my cultural background searching for examples of lifestyles that diverge from those of our idealized ancestors.

I related to how Kohen wrote about being a minority within a minority. In Flower of Vlora, she holds family memories of being sheltered by Albanian Muslims during the Holocaust alongside the difficulty of antisemitism. Growing up partially in an Albanian Muslim family, I was similarly very aware of how Albanians were and continue to be treated as minorities, while I also experienced antisemitism. It wasn’t just seeing my own experiences reflected back to me; it was that those experiences were reflected in a person who I’d grown up viewing as categorically different from me. As Albanians, Greeks, Jews, and even Turks, any overlap, shared history, shared humanity, and shared culture is so often denied in anger. But in Kohen’s memoir she is at ease moving between Greek and Albanian identities. It was a revelation to read about a Jewish woman who was Greek, Albanian, and Jewish. Far from polar opposites, my identities and histories have always been rushing and flowing, mixing together through the alchemy of empathy and history. Similarly, there is no identity for Kohen to return to that is not a confluence of the worlds that influence and inspire her.

Throughout the book, Kohen fights for her right to flourish in the wake of Albania’s historic antisemitism and the misogyny she faces as a career woman. Her dentist boss refusing to take her advice on how to bring more money into his dental practice results in her being paid less than she could be. She knows, then and there, that she won’t just be a dental assistant—she will be a dentist with her own practice.

Kohen’s warm candor also extends to her portrayal of Jewish experience. So often, American Jewish narratives portray Jews as being more authentic and religious the further back in history they live. Yet at no point is there a moment of grappling between her Jewish identity and some separate secular world. Kohen is a fully Romaniote Albanian American woman in a contemporary world living in a community that holds diverse expressions of Jewish identity under the same roof.

Watching Kohen’s interviews and book tours, I am happy that her work is receiving deserved attention. There is very little literature about Albanian Jews, let alone work written by a Jewish woman, that portrays an authentic Jewish life that is impacted by the secular, scientific, and sacred. Her life’s story is a reminder to me, as an Albanian-American woman, that I have it in myself to survive and to thrive in the most difficult of circumstances. Kohen is fearless—and she will inspire more Jewish women to be just that.

As she writes in her book:

“Very Albanian, and very Jewish.”