Maraviglia's Fifteenth-Century Prayer Book

The story of the siddur described in this blog post by Dr. Evelyn Cohen is important both as an object—a testament to women’s participation in fifteenth-century Italian Jewish ritual life—and as an exemplar of how digitized resources can build and develop knowledge communities.

Maraviglia’s siddur came to the American Trust for the British Library (ATBL)’s attention as a British Library loan to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston’s current, groundbreaking exhibition, Strong Women in Renaissance Italy. Strong Women upends assumptions about and expands audience understanding of women’s active engagement with all facets of life in Renaissance Italy, across faiths. But it was Maraviglia’s siddur, and its illustrations’ quiet but powerful challenge to any presumption of fifteenth-century Jewish women’s devotional passivity, that turned this text into the exhibition’s “guest of honor.”

Dr. Marietta Cambareri, the exhibit’s curator, discovered Maraviglia’s siddur and its importance by chance: exploring The Polonsky Foundation Catalogue of Digitised Hebrew Manuscripts, she happened upon Dr. Evelyn Cohen’s blog post analyzing the text. From there, Dr. Cambareri’s journey to engage with the siddur resulted in reconnecting with Dr. Cohen, whose enthusiasm and encouragement gave her, in her own words, the “courage” to ask for the exhibition loan.

These conversations among Dr. Cambareri, Dr. Cohen, and the British Library’s Lead Curator of Hebrew and Christian Orient Studies, Ilana Tahan, resulted in the siddur's journey to Boston—a happy result of intellectual networking among brilliant, passionate female scholars, and a realized promise of digitized collections’ capacity to generate new dialogue and research. Maraviglia’s siddur will return “home” to the British Library after the close of the MFA exhibition, where its story—and its implications for the active ritual life of fifteenth-century Jewish Italian women—will be re-told in the context of the Library’s forthcoming show on Medieval women’s books and lives.

Though misogyny and patriarchal systems historically work against women’s ability to acquire education and to advance within governance or communities, it’s important to remember that, regardless of the century, people remain people. The women and girls who sought opportunities for learning and leadership and were able to access them; the supportive husbands, fathers, brothers, and teachers who committed to the advancement of the women in their lives; women’s intensity of desire to be an active part of the world around them: these archetypal people exist today, just as they existed in the centuries before. Maraviglia’s siddur underlines the fallacy of assumptions that Jewish women’s leadership in typically male-dominated rituals is a development of the modern era, and anomalous in centuries past. While much will remain unknown about Maraviglia’s siddur, its story, and the potential gender parity in aspects Jewish life suggested by its pictures and commission, connects us to a long-gone era, and creates space to wonder: What if the past was different from what we thought?

Elizabeth Berkowitz, MA, PhD

Executive Director, The American Trust for the British Library

***

The exceptional collection of decorated Hebrew prayer books in the British Library contains an intriguing work produced in Italy in 1469 CE. It was copied by the noted scribe-artist Joel ben Simeon, who most likely executed its decoration as well. At least 30 manuscripts have been associated with Joel. Inscriptions in several of them specify that he either copied the text, created the illustrations, or did both. Other codices in which the scribe and artist are not identified in the text are attributed to Joel based on similarities to the scribal practices and artistic style in the signed works.

Within the text, Joel specified that he wrote the prayer book, which he referred to as the tefilah (Hebrew for prayer), for Menahem ben Samuel and for his daughter Maraviglia. The first part of the manuscript, which would have contained the prayers recited daily, is missing. As a consequence, the book now begins with the last page of the text of the daily evening prayer and continues with prayers recited on the eve of the Sabbath.

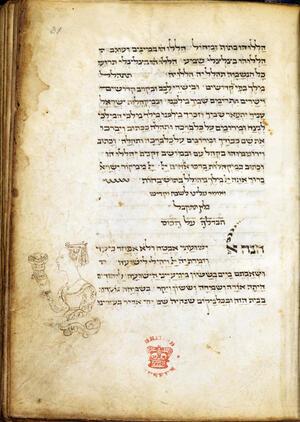

The first intact illustration in the manuscript appears next to the havdalah prayer recited over a cup of wine at the conclusion of the Sabbath. An elegantly attired young lady, probably a reference to Maraviglia, is portrayed raising an elaborate chalice with her right hand. This scene initiates what is the most extensive extant cycle of representations of women participating in Jewish religious rituals known from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

The next section of text contains the prayers recited monthly upon the appearance of the New Moon, followed by the liturgy for the festivals of Hanukkah and Purim. No illustrations were included in this part of the manuscript.

As was often the case in fifteenth-century prayer books from Italy, the greatest concentration of images accompanies the Haggadah, the text read during the seder, the ceremonial meal that is celebrated on the first two nights of Passover (except in Israel, where it is celebrated only on the first night.) Eight scenes illustrate different aspects of the Haggadah text.

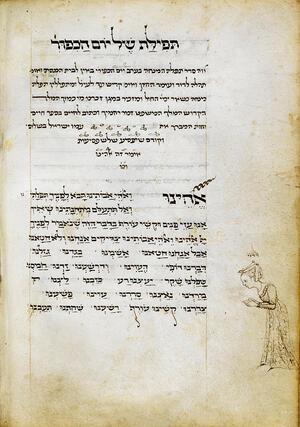

The first image in this section of the manuscript depicts the raising of the seder basket containing the ceremonial foods consumed during the seder. Most easily identifiable are the three required matsot (the plural form of matsah, the unleavened bread eaten during Passover.) The placement of the basket as it appears here, next to the passage in Aramaic that begins with the words ha-lahma anya (this bread of affliction) is common in manuscripts of the period. The way in which the scene is depicted, however, is unusual, reflecting that this manuscript was destined for use by a woman. Rather than depicting exclusively male participants, as was customary, in this image a young man and woman raise the basket. Joel infused the scene with a humorous note, with the couple gazing into each other’s eyes rather than at the basket and its contents.

The next two illustrations comprise rather standard scenes that relate to the retelling of the story of the Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt: They portray an Israelite slave carrying buckets and an Israelite baby being cast into the Nile. Hebrew inscriptions placed within banderoles (speech scrolls in the page margins) identify both scenes.

A subsequent section of the Haggadah text presents the opinions of various rabbis concerning the Exodus. The passages recounting the views of Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Akiva are accompanied in the outer margin by imagined portraits of the two sages. This imagery is traditional, as is the next illustration depicting Rabban Gamliel, who spoke of three things that must be discussed in order to fulfill the obligation of recounting the Exodus . The second item is the matsah, which in many Haggadot was accompanied by an illustration of a man raising the round, unleavened bread. In this manuscript, intended for the use of Maraviglia, a young woman is shown raising the matsah instead.

The last element discussed by Rabban Gamliel is the maror, the bitter herbs. The illustration for this passage in the text is conventional, with a young man—rather than a woman—shown holding a bunch of leaves while pointing to the text that is recited about the maror.

After the conclusion of the text of the Haggadah and the prayers read during the Passover festival, and immediately before the section that deals with the festival of Shavuot (the Feast of Weeks), the scribe copied the benediction recited when the Omer is counted nightly for forty-nine days from the second day of Passover until the day before Shavuot seven weeks later. (Omer refers to a measure of barley that was brought as a sacrifice during this period at the time the Temple in Jerusalem existed.) In this uncommon illustration, the person pointing to the text to be recited is female.

The final image of a woman in this manuscript appears immediately before the evening service for Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement). In the outer margin a young lady, her hands posed with her palms together in a gesture of prayer, bows from her waist while reciting a vidui (confessional prayer). The Hebrew word for this prayer is inscribed above her head.

One of the most captivating aspects of this prayer book is found in figures drawn in the margins of two pages, each of which was later partially erased. In the manuscript’s current incomplete state, the first canceled image now stands as the first illustration. It appears next to Psalm 34, recited during the morning service of the Sabbath. Although much of the figure was scraped away, the outline of King David wearing a crown is still discernible, as is the faint contour of his head resting on his right hand, and his bent left leg. The same pose was used for a sleeping figure in the Rothschild Mahzor produced in Florence in 1490 in a section of the manuscript containing illustrations in the style of Joel ben Simeon.

This scribe-artist sometimes employed visual puns that invited double meanings for words. In the Maraviglia Prayer Book, the Hebrew words at the beginning of the psalm, le-David be-shanoto (of David when he changed the essence of his person) refer to King David when he feigned madness. In the accompanying illustration, traces of an inscription remain in the banderole above David’s head. Modern multispectral images make clear that the text is a repetition of the Hebrew phrase, but unlike the appearance of the words in the main text, here they are not vocalized. They therefore can also be read as le-David be-shenato (of David in this sleep), which is what Joel playfully depicted. It is possible that a later reader, unaware of Joel’s good-humored punning, deemed the figure in the margin inappropriate and had it scraped off, albeit not completely.

A second erased image appears within the liturgy of the Jewish New Year, in the outer margin next to the text that is recited when the shofar (ram’s horn) is blown. Only a faint outline of the shofar remains. With multispectral images, the details of the bust-length figure of a young man wearing a cap and blowing a ram’s horn are visible. A comparable image appears in the Rothschild Mahzor, where a youth with a similar hairstyle and cap is shown in the same pose. As the illustration in the Maraviglia Prayer Book is appropriate, its removal is surprising. The British Library’s multispectral image from 2015 has brought to light an unusual feature in this illustration—a long plume attached to the man’s hat. The feather, utilized to clean the shofar, is not found in other extant illustrations in Hebrew manuscripts

Although impossible to ascertain, a later observer may have misconstrued the plume in the fifteenth-century cap to be female attire and mistakenly concluded that the image was that of a young lady. As women were not allowed to blow the shofar ritually, the image would have been viewed as inappropriate and therefore removed.

The Maraviglia Prayer Book provides important documentation of religious practices among women in fifteenth-century Italy. While the illustrations depicting a young lady participating in Jewish rituals are unique, so is the appearance of the feather used by the shofar blower, which only recently has been revealed.

Maraviglia's siddur was digitized through the generosity of The Polonsky Foundation. The Foundation ensured the broad dissemination and contextualization of the British Library's digital Hebrew manuscripts collection with its support for a scholarly digital catalogue, The Polonsky Foundation Catalogue of Digitised Hebrew Manuscripts. Over the years, the ATBL has also provided incremental support for the Hebrew manuscripts collection at the British Library, including cataloguing support in 2008 and 2009, digitization support, and curatorial support (most recently in 2021).

The ATBL is proud to continue the dialogue on Maraviglia’s life and the narrative of her siddur through a virtual conversation between Ilana Tahan and Dr. Cambareri.

This blog post was lightly edited and republished with thanks to Dr. Evelyn Cohen, Ilana Tahan, and Dr. Marietta Cambareri. The original version can be found here.