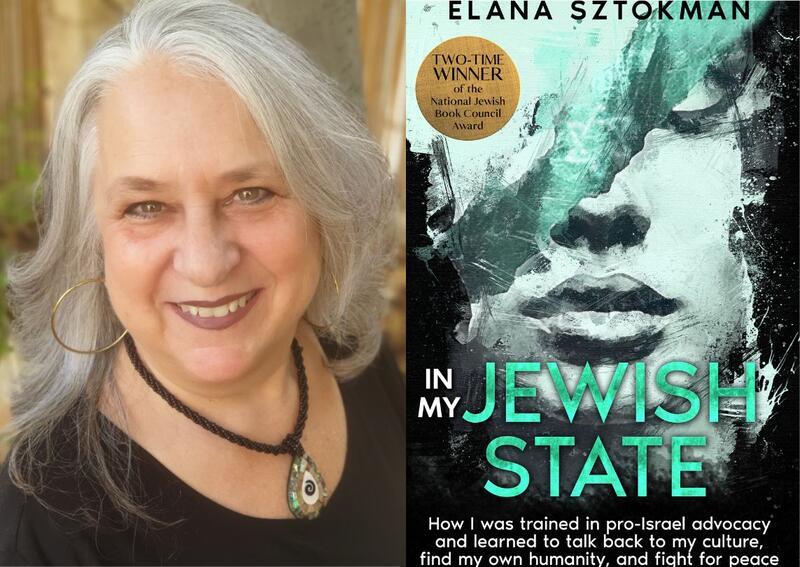

Elana Sztokman on Her New Book, "In My Jewish State"

Dr. Elana Sztokman is a sociologist and the award-winning author of The Men's Section: Orthodox Jewish Men in an Egalitarian World and Educating in the Divine Image: Gender Issues in Orthodox Jewish Day Schools. Her subsequent books have dealt with sexual abuse in Jewish communities, body image in Judaism, and religious radicalism. She has lived in Israel for the past 35 years.

In her new book, In My Jewish State, Sztokman describes her political transformation, explaining how she came to understand that only a moral, humanist approach to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict can bring about a viable solution for both peoples. I spoke with her about the transformation of her religious and political views, her work with Arab-Israeli activist Eva Dalek, and her insights into what is missing when women are excluded from peace negotiations.

Janice Weizman: Can you start by telling us about the world that you grew up in, and slowly made your way out of?

Elana Sztokman: I grew up in New York in the religious Zionism of the 1970s and 80s. It was a post-1967 era of Israeli infallibility, Salute to Israel parades, [Orthodox youth movement] NCSY, [religious Zionist youth movement] Bnei Akiva, Soviet Union demonstrations, and Rabbi Avi Weiss chaining himself to the White House. We Orthodox Jews believed that we were better than everyone else, Israel was proof that we were in the period of the ingathering of the exiles, Israel was part of God’s plan, we had the secret to knowing what God really wanted, and it was whatever we were doing.

JW: How has that background shaped the way you view the Palestinian-Israeli conflict?

ES: We had mandatory classes in Zionism in ninth grade even though most kids probably hadn't been to Israel yet. The classes were aimed at instilling the most intense right-wing version of history, which was cast as “pro-Israel.” Anything less was cast as “anti-Israel” or “pro-Palestinian,” which were effectively seen as the same thing. We learned that Palestinians are not a nation and don’t really exist as a people, that Arabs (that is, Palestinians) have no culture and no history other than bloodlust and hatred of Jews, that Jordan is really part of Israel, that Arabs lie and can’t be trusted, and that Israel has the most moral army in the world. Things like that. Unequivocal, unyielding, and tied up in a neat package that was very difficult to unpack. We had all the answers before we even knew what the questions were.

JW: In the book, you describe how over the years, your thinking has shifted from what is considered “right-wing” (i.e., Israel should annex the West Bank and Gaza) to “left-wing” (i.e,. a two-state solution). Can you speak a little about the change in your thinking and what led to it?

ES: I don’t really like the whole right-wing/left-wing configuration. This right-left binary basically sees a kind of zero-sum game of support. Either “us” or “them,” either supporting Israel more or supporting Palestinians more. But it’s not like that for me—or for a lot of others whom I’ve come to see as allies. It’s not that you’re either pro-Zionist or pro-Palestinian. It’s whether you’re pro-humanity or pro-my-tribe-only. Or whether you’re pro-compassion or pro-violent militarism. I have more in common with Palestinian Muslim and Christian women who are anti-violence and believe in the possibility of peace based on shared values of empathy, freedom, humanity, and justice, than I do with my landsmen and landswomen who hang on to fearful, vengeful, stereotypical thinking about the “other.”

How did I get here? By letting go of all that fear, all that macho, vengeful jingoism, and the need to prove that Palestinians are all liars. And instead of that, seeking out actual people who are “different” from me, people who I was taught to view as dangerous “enemies,” and actually connecting. It’s about listening and paying attention and opening our hearts to other human beings as human beings. It’s also about growing up and thinking for myself/

JW: How have the October 7 attacks impacted your political thinking?

ES: Despite the enormous trauma, I did not let these events turn me to a place of vengeful thinking or calls for collective punishment or any of the shocking statements we hear from so-called leaders and all over social media calling for monstrous violence. That is not the answer. If anything, the events of October 7 have sent me further towards peace activism and the urgency of promoting a long-lasting solution. They have reinforced in me the need for listening to human beings as human beings and engaging with Palestinians in real discussions about the long-term future of this place.

JW: Much of your work revolves around the place of women in traditional Judaism. Do you feel that issues of gender are in any way relevant to the Arab-Israeli conflict? If so, how?

ES: Yes. My experiences with feminism trained me in seeing people who are deemed lesser, whose lives are deemed invisible or expendable, who are cast in the political rhetoric as people who need to be punished or controlled. When I first started to understand just how much we Jews/Israelis systematically cast the entire Palestinian people as less human, as evil liars who don’t deserve to live, I started to identify with that experience of being cast out by people with power as not deserving, as not worthy, as just lesser—less good, less human. I think the feminist lens has helped me see issues of justice in very important and significant ways.

JW: Honestly speaking, I felt that your discussion of how Jews and Palestinians are portrayed in Jewish media doesn’t give enough weight to both the trauma that Israelis and Jews have experienced, and the notion that Hamas has stated (and some Palestinians would agree) that it won’t tolerate the existence of a Jewish country in the Middle East. Would you like to respond to that?

ES: It’s a terrible thing for us to equate 2.2 million Gazans with violent terrorists. Even if violence is written in the Hamas charter, that doesn’t mean anything about real people living real everyday lives. The overwhelming majority of Palestinians want the same things we do—to have a normal life, a home, family, friends, land. But the enemies of peace like to hold up the Hamas charter as “proof” that “all” Palestinians are terrorists. That is so wrong.

I’m saying, we don’t want to be judged by the worst ideas that our people have ever put forward. We don’t want people to look at the most evil Jews and think we are all like that. We don’t want people to say, “Well, you Jews have Harvey Weinstein and Bernie Madoff, so you all must be really awful people who deserve whatever awfulness comes your way!” So why is it okay for us to do the same to Palestinians? We need to understand that “Palestinians” are not all one thing, and certainly not all terrorists. They are first and foremost human beings. There are millions of Palestinians who are exactly like us, who just want to live a normal life in this land. We would all be better off if we seek out and find human beings among us.

JW: What I found really compelling about the book was your insistence on a humanist stance, even in the face of a murderous enemy. What would you say to those who might call your position naïve?

ES: I’ve been living in Israel my entire adult life. My kids all serve in the army. There is nothing I haven’t seen in the past 35 years as an Israeli citizen, as a political activist, as an educator, as a parent. I think I understand all this as closely as anyone can. Calling me “naïve” is just an excuse not to listen, to stay stoic in the fear and inhumanity.

JW: In the book, you discuss your recent partnership with Arab-Israeli activist Eva Dalik. What traits or experience do you think women can bring to the situation that are currently missing?

ES: This war is very gendered. All the decisions about it are being made by men, with zero women around the table in the security cabinet, in the IDF brass, or on the negotiation teams. Rachel Goldberg-Polin [mother of hostage Hersh Goldberg-Polin, who was killed in Hamas captivity] says that had women been in decision-making power—had mothers of hostages and mothers from Gaza sat around the table—the war would have been over and the hostages home within a week.

And so, last January, a group of Jewish-Israeli and Palestinian women got together and formed Forum 1325 in order to advance a different way of thinking about the conflict, to get women into real positions of power, and to end the bloody war. During our months of strategic thinking, I got together with some partners, including Eva Dalak, a Palestinian citizen of Israel from Jaffa who was consulting Forum 1325, and we created an English language podcast called Women Ending War. We have interviewed Jewish, Muslim, and Christian women from different locations in this war, sharing their many strategies for crafting a different future. We are now on our third season, and I am working with several cohosts—Dr. Fakhira Halloun, an expert in conflict resolution from Daliat Al Carmel, and others—in order to get the message out that there IS another way.

It's definitely challenging work, but it feels like the most urgent work in the world. The fight to hang on to our humanity even while the world is burning around us—that is not always easy. But we need to do it. There IS another path, and we women can and ought to be leading the way. In fact, I think it's possible that women's leadership may just be the thing that turns this whole story around.