For Czarna

Aunt Czarna, this is the story of your only son. He held your hand as you walked through the streets of Lens, the stoic expression on your face belying your inner terror. Another ten-year-old boy, a classmate, ran pointing and shouting that he’d report you for not wearing the star. You grasped your son’s hand tighter. “Keep walking. Ignore him,” you said. By some miracle, the boy did not reappear.

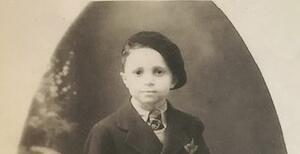

At the train station, there were joyous sendoffs. Waving, smiling parents blew kisses to excited children embarking for a summer in the French countryside. You had no choice but to trust the Red Cross director accompanying him. You helped your son with his bag, and held him for an extra moment before he boarded. Your last glimpse was his face plastered against the window, tears trickling down his cheeks. On the platform, you stood perfectly still, not waving, crying or wringing your hands. Had you done the right thing? Of this, you were certain. Would he be okay? Of this, you were not.

At home, you gave a curt nod to your husband, wrapped in his prayer shawl all morning, davening for your son’s safety. Years earlier, your siblings in America had begged you to come, sent you tickets, but now it was too late.

Placed on a widower’s farm in the Jura Mountains, your son helped in the fields and fed the chickens. When asked his religion, he said “Protestant” and attended church with the family every Sunday. A month into his stay, your son overheard the live-in housemaid cavorting with German soldiers, speculating that he was a Jew because he received no letters from his family. Your clever boy convinced the farmer to send him into town on an errand and got word to the Red Cross director. She removed him the next day, driving him to Valloires, an abbey-turned-preventorium for children prone to tuberculosis. The oldest pear tree in France, planted by Cistercian monks, grew next to the dorms. Three nurses were the only ones aware of his identity.

Your own story ended around this time, September 1942, shortly after the Jews of Lens were deported to Auschwitz. The reports that filtered back after the war were inconsistent on the exact date of your death, or your husband’s, or your three remaining siblings’ in Europe, their spouses’ and babies’.

There was little time for normal school subjects at Valloires, though your son excelled at catechism and taught the younger boys. During daily mass, he pumped air into the organ, lavish angels and pears carved into its case. Later, he understood the adults assigned him these tasks so no one would ask why he never took communion, though by this point he secretly wished to become Catholic. He witnessed hundreds of aerial strikes and the occasional dog fight. British pilots parachuted from the sky.

In 1944, the Germans arrived at Valloires to set up an underground hospital. A soldier grabbed your son’s arm: “Bist du ein Jude!” Your son shrugged his shoulders in typical French fashion. “Je ne comprends pas,” though he understood perfectly. Twice the soldier repeated his accusation and twice your son shrugged, displaying your instinct for survival.

One morning, he woke to find the Germans gone, vanished miraculously into the night.

On the day the Canadian convoy began rolling past the abbey—an incessant parade of trucks, jeeps, tanks and artillery that would last for days—your son felt relief, but not joy. His happiest memory of that time was seeing l’abbe, the director’s brother, wearing the armband of the FFI (French Forces of the Interior). How glorious, he thought: our very own priest in the French underground!

Your son passed two years living with a Jewish family in Lille, waiting for his papers. Each day, he visited the repatriation center, where the names of Jews liberated from the death camps were read aloud. Your name was never called. Little by little, he understood: Of his 35 immediate family members in Europe before the war, he, alone, had survived.

He reached the safe shores of America in the spring of 1947, a few months before his fifteenth birthday. In Bridgeport, your remaining siblings adopted him as one of their own. He lived, for spurts, with Pearl or Fanny or Dave or Max and their growing families. The cousins were counseled not to ask any questions.

Your son finished his education, married, and moved across the country to faraway California, where he found work as a media executive. His children—two boys and two girls—learned by example: Practice forgiveness. Look for the good in others.

He never considered himself a survivor because he hadn’t been in the camps, but he struggled. Until he chanced upon an article about the hundreds of Jewish children hidden during the war, three decades later, he thought he was the only one. He shared his experiences for the first time in 1991, when the cousins begged him to write them down. “The question ‘why’ is still here with me every day of my life. Why? Why? Why?” he wrote. “Why me and not Toba’s innocent baby with the big blue eyes?”

Aunt Czarna, you wondered if he would be okay. There’s no simple answer. He felt no joy in surviving. He drew strength from you daily, for his entire life. Your memory was his blessing: your kindness and your bravery.

Hear the words of your granddaughter, in 1999, introducing him at her high school: “Instead of emerging from the war full of hatred and anger, he has emerged as a man of love and understanding.”

He passed away in 2001 at age 69.

Do not weep, Aunt Czarna. Take comfort from the angels who protected him. From the man he became, loved and cherished. Your story, and his, live on through your grandchildren and other relatives. They’ve visited the abbey and labored to bring recognition to the nurse who saved his life. Behold the lives you saved, the worlds created by sending him on that train on that day. Be proud of his story, and your own.

In memory of Czarna Glantz Kleinhandler (1901–1942) and Joseph Kleinhandler (1932–2001); In memory of and gratitude for Thérèse Papillon (1886–1983), recognized by Yad Vashem for saving Joseph and three other Jewish children during the war.

The tears are stopping

Thank you so much for sharing this story. It is the perfect blend of bitter and sweet for the start of the New Year. It really touched me.