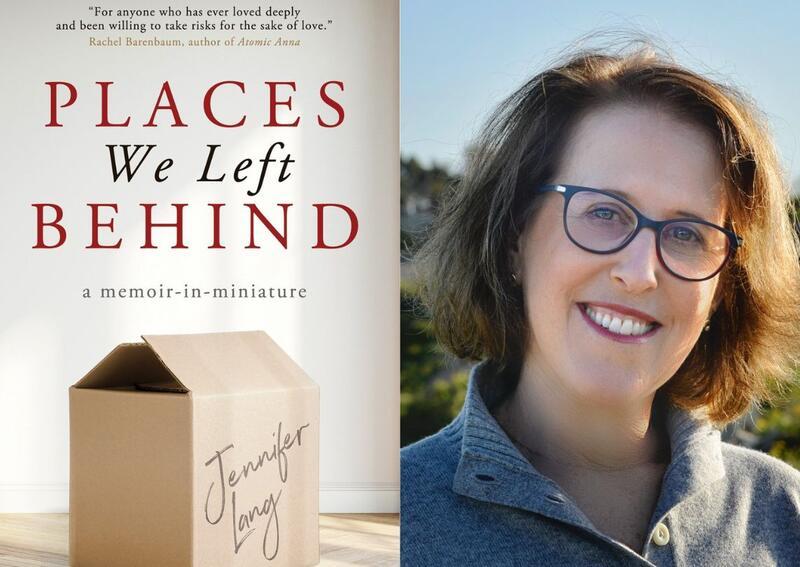

Q & A with Jennifer Lang, Author of "Places We Left Behind"

The summer I turned sixteen, my mom registered me for an Israeli tennis program on one condition: that I wouldn't fall in love with an Israeli and set my sights on making aliyah. I kept the deal, falling first for an adorable American who packed his passport on the way back to the US and then for my high school prom date, who eventually became my husband.

A new memoir by Jennifer Lang helps me imagine the scenario my mom had feared. At 23, Lang fell head over heels for French-born Philippe during the First Intifada in Israel. Theirs was a whirlwind romance, with Philippe suggesting they live together just eleven days after they met. A day after their wedding, en route to France, Philippe asks, “Do you feel like we just made things complicated?”

They had, as readers will learn in Places We Left Behind, a micro-memoir told in reflective vignettes of the couple's globe-trotting life and conflict over their differing Jewish observance and which of three countries (America, Israel, France) to settle in with their three children. Lang longs to live in the US, where she can raise her children in her “mother tongue.” Philippe, who grows increasingly more observant, “feels dead in America” and wants to move to Israel. For many years, a resolution seems impossible.

JWA spoke with Lang, via Zoom to Tel Aviv, where she lives (with Philippe) and leads the Israel Writers Studio.

JWA: What made your Jewish identity so strong?

Jennifer Lang: I grew up on the West Coast, with Russian and Romanian grandparents on my dad’s side and American-born grandparents on my mom’s side. Going to temple on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur was non-negotiable, but I knew nothing about keeping kosher. On Passover, the Ding Dongs, HoHos and Pop Tarts were all moved to the basement freezer; Manischewitz filled the cupboards for the week. Then, I’d go to school and swap my matzoh sandwiches with my friends for their Wonder Bread sandwiches.

Who I am as a Jew comes from the Reform movement. I spent many years at camp as a camper and counselor and was very involved in my youth group. I visited Israel for the first time I was five, pulled from the last month of kindergarten to meet my extended family. We returned when I was ten, on a family mission, and I visited again when I was fifteen, on a six-week youth group trip.

JWA: You had this strong pull to Israel, but as a young wife and mother, you found the country “brought out the worst in you.” You’ve lived in Israel since 2011—do you still feel that way?

JL: It was only in the letters that my mom, aunt, and very close friends returned to me later as I became a writer, that I was able to reacquaint myself with my 20-year-old self, to see the passion I had for this country, and that I had the tools to stay.

After living in France after college, I decided I didn’t want to live the life of an expat. I missed my parents and friends. While I awaited graduate school decisions, I spent five weeks in Israel trying to repair my relationship with my brother. By then, Israel was my brother’s country. He was on his way to becoming very religious, and I didn’t want anything to do with it. I was very defensive, walls up. I was battling it from the moment I landed. I was resisting Israel on so many levels—personally, professionally, and religiously.

I struggled here for a long time. When I fell in love with Philippe, I let go of my dream of graduate school in America. Instead, I did a master’s in international relations in Israel and we made a very full life here. I was fluent in Hebrew, but I’d fall apart when I would ask for directions and strangers would notice I was American. I couldn’t handle the invasion of personal space and the lack of manners, even the lines at the grocery store, where Israelis would step forward, insisting they were there first. So many things got under my skin and I let them.

With age and confidence, I’ve toughened up. I’ve found my path professionally. My children are grown, so I’m no longer vulnerable raising little kids here. Today, if I ask a question in Hebrew, and someone answers in English, I no longer feel like it's a comment on my Hebrew. My whole perspective has shifted; I now look through a different lens.

JWA: How did you come to choose micro-memoir as a form?

JL: I started with a traditional narrative, a 65,000-word manuscript I’d written during my MFA. The editor I worked with thought I’d created a character [in myself] that the reader could root for, one who wasn’t ambivalent, who had her good and her bad sides. But I needed to flesh out the secondary characters: my husband and my kids.

I knew the editor was correct in her feedback. Yet, my oldest son, who’d joined the Israeli army and become a well-known teen-preneur in high-tech, asked me to stop using his name in my writing. I understood and respected that, but it presented a real obstacle.

I put the work away for months. I became an editor at Brevity Magazine, reading nonfiction stories under 750 words, and I took an intense ten-day online class in writing condensed “flash” stories. I began to chisel and cut my prose, to get smaller and smaller to find the heart of things. Finally, I turned the camera on myself, not just writing about my marriage, but about my individual journey too. At a critique partner’s suggestion, I submitted to publications that were accepting “experimental prose” like mine and received encouraging feedback.

JWA: You use a lot of different visual tools—charts, lists, poems. I loved how you struck out certain lines that seemed darkly honest or revealing. For example, this line: We left [Israel] for Philippe, but we’ve stayed away for—because of—me.

JL: The word is shame; I felt ashamed. The strikethroughs were thoughts and feelings that were hard to admit and hard to stand by, but I felt the reader should know.

JWA: For many years, you and Philippe “turned the where to live and how much Judaism to live by conversations taboo.” How did you avoid these critical discussions?

We came to California for a year and we just stayed. We weren’t talking about it, we got pregnant again, and we stayed. We pushed it under the rug. When friends or family would ask about our plans, Philippe would look at me and say in French, which no one else understood, “I don’t want to talk about it.”

Therapy pushed us to talk, but we couldn’t find a resolution. Eventually, for Philippe’s work, we had to move, either to Israel or New York. I picked New York, but only if we could buy a house, because I wanted to feel rooted.

JWA: What a pang we readers feel when you leave California, where you’re most comfortable, and move to New York, and nine weeks later, the terrorist attack on 9/11 occurs. How did that event affect the where to live debate?

JL: We stayed for another ten years, but after 9/11, I’d lost my ammunition. I could no longer say that Israel wasn’t safe, because America wasn’t safe either.

JWA: What advice would you give to your younger self or someone entering what you call a “mixed marriage”?

JL: Hold onto yourself. I am all for falling in love. I’m a big proponent of following your heart, but hold onto your identity. Don’t just give up and give in. It took me until my early 50s and for an editor to say, If you let Philippe apologize, and you accept his apology, you also need to apologize to yourself and accept it. I was so angry that I couldn’t understand it was my fault too. I pointed the finger instead of taking responsibility.

JWA: You ask many profound questions in your writing. May I plagiarize you and ask you to answer your own questions?

JL: Sure.

JWA: “All I want to understand is how, after growing up in the same house-street-city-county-state-country-continent, have I ended up so rootless?”

JL: My parents were born and bred in California, but they opened us to the world. My mom started me in a French immersion program from age 6. We weren’t wealthy—maybe we were comfortably middle-class. We took international flights when our friends [didn’t] and we had foreign exchange students live with us. About our trips to Israel, my parents would say, “You can’t live your life out of fear or you won’t live at all.” Studying abroad in Paris for junior year changed me. Paris was so free and colorful. I didn't want a uniform, yuppy American version of adulthood

How did I end up so transient and rootless? My parents showed me the world.

JWA: “Does every young adult have to flee and grow up in order to look back with longing and appreciate their place of birth? Does everyone reach a point where they realize no place is perfect, there is no utopia?”

JL: I think so. The Northern California that I left behind is no longer the same, with its homelessness, and wildfires, and the aftermath of COVID. I feel nostalgic and sad, but I have no desire to go back.

JWA: I love the self-talk you offer, reminding yourself that “…[c]hange can be difficult. That it means loss. But [also] that we are fortunate. We have choices. Change can also bring good. The good part is up to me. To us.” What other mantras have guided you?

JL: My mom raised me with mottos like There’s no harm in asking, There’s nothing to lose and What’s the worst that can happen? I’ve internalized these mantras and I hope I’ve raised my kids with them. They’ve certainly guided me in this publishing process.

Friends have described me as resilient in the face of adversity. The first time I felt that as an adult was when I was newly married, running for shelter, in the middle of the night, during the first Gulf War, putting on a gas mask, my parents calling from California, asking if I was okay. I was not okay, but I had to fake being okay. It took me moving back to Israel to realize I had PTSD from that siren that I needed to work out. I’m happy to say when I hear a siren, I have less of a freak out. And the version of that siren that happens in Israel every year on Memorial Day, I now find very beautiful and powerful.

JWA: Your second memoir will be released next year. How did you decide to separate your life into two stories?

JL: I realized I had two parts of my journey to share, one from 1989 to 2011, which is Places We Left Behind, and another from 2011 to 2018, after we settled in Israel. Landed: A yogi’s memoir in pieces & poses, is also unconventionally written, and is about my seven-year search, on and off the yoga mat, for peace and for home, which I come to understand is not geographic.