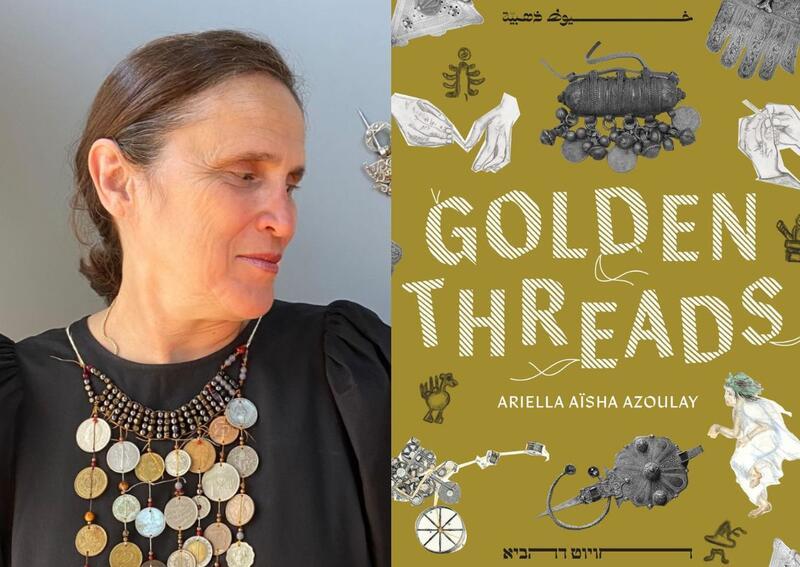

Q & A with Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Author of "Golden Threads"

JWA chats with Arielle Aïsha Azoulay, a professor at Brown University and the author of Golden Threads, a new children’s book that explores the melting pot of Jewish and Muslim artisan communities in 1920s Morocco. The book’s protagonist, Rachelle, is a young Jewish girl who connects Jewish and Muslim craftspeople as they work to protect their way of life from the perils of industrialization.

JWA: Congratulations on the publication of your book, Golden Threads! Tell us about the story and the process of creating the book.

Ariella Azoulay: It is a book I would have loved to have read when I was a child, and as it was not yet written when I was a mother, I had to write it when I became grandmother. It is a book about a group of girls who grew up in the mellah (Jewish quarter) of the city of Fès in Morocco at the beginning of the twentieth century. These girls’ families carried on the centuries-old Maghrebi traditions of craft, serving mainly as jewelers and gold thread spinners.

One day, a European machine capable of preparing golden threads with almost no human labor arrives in Fès and seriously threatens the livelihoods and traditions of these girls’ families and community. The entire community of Jewish and Muslim craftspeople and their children go on strike, which leads to the interdiction of the machine. The story is narrated from the point of view of Rachelle, who was eight years old during the strike. Restaging the Jewish Muslim world through the lives of the children of artisans was my way of telling a story about a world that was destroyed, without accepting the colonial verdict that assumes that this world is over forever. What the girls encounter amidst a rich world of learning is the antithesis of the education they will be provided within the state’s schools.

JWA: This is your first book for children. What inspired you to pursue this project?

AA: The understanding that children can grow up today knowing almost nothing about the rich Jewish Muslim ancestral world—let alone that they, their ancestors, and their neighbors still belong to it—motivated this project. When I was writing The Jewelers of the Ummah: A Potential History of the Jewish Muslim World, I felt that so many of the stories that I was able to gather, revive, and make part of my world (despite the fact that they were not transmitted to me) are stories that my children and grandchildren could have grown up knowing had colonial projects not kept them apart from them.

We are living in a world where genocide can be supported overtly by liberal states and organizations, and where imperial and capitalist entrepreneurs act as if they can force us to be replaced by their dangerous AI technologies because people’s capacity to say “no” is threatened. This story of a community that came together to say "no" to what was depicted as “progress” is an inspiring story for children. It enables them to learn about and imagine themselves as capable of saying “no,” of opposing—at the right moment and along with others—what they know is unacceptable and unpardonable.

JWA: The book is a unique blend of prose and visual storytelling, with illustrations by Hagar Ophir and design work by Haitham Haddad. What drew you to telling Rachelle’s story in this medium?

AA: Working with Hagar Ophir and Haitham Hadad was a true gift. It is, I think, the first children’s book any of us have worked on, so we each felt free from prior assumptions of what works or doesn’t work for children and followed our intuitions. The first draft of the story had an unknown narrator, and it was my sister who advised me to change it to Rachelle’s first-person voice. In enjoying the privilege of telling the story to my granddaughters multiple times, I immediately understood that my sister was right. Rachelle cannot forget the world she experienced prior to turning eight, when the mellah started to fall apart, and she tries to make sense of this radical change through her own experiences and what she understands from the conversations she overhears between adults. It is through her eyes and voice that we get to see the invasiveness and destructiveness of Western modernization, which is often described [in the book] as the “introduction of machines.”

JWA: Something I found very powerful was your inclusion of an alâqa, a traditional earring worn by the children of jewelers in the Jewish Muslim community in North Africa. In your author’s note, you mention that the drawing of the alâqa is detailed enough that it can show someone in the present day how to reproduce the earring and continue this tradition. What other resurrectable artifacts might someone find in Golden Threads?

AA: Sharing this DIY drawing of the alâqa is, in part, a way of decentralizing the museum. [The museum is often held up] as the authoritative institution that has the right to determine that our heritage is only what it holds captive due to massive plunder from the Maghreb [the region of Western and Northern Africa that includes Morocco]. The alâqa was meaningful within the Jewish Muslim world, where the Jews were the jewelers, and the vision of this book and of The Jewelers of the Ummah, is that this world is possible again. Both books reflect upon how being a jeweler or an artisan is not only about making objects, but a way of being in the world with others, a way of caring for the world with others, a way of refusing to participate in the race of genocidal capitalism. Everything that we could do with our hands, with our bodies, together with others, inspired by bodies of knowledge that we have been told are obsolete, is already a rehearsal in resurrecting ancestral worlds against this world run by destructive corporations.

JWA: Grandmothers and the theme of inheritance play a strong role in Golden Threads. What do you hope your eight grandchildren will inherit from you?

AA: I’m not sure I can answer this question directly, as my writing of this book was not motivated by a wish for them to inherit something, but more by a desire for us, diverse Jews, to liberate our imaginations from stories that were told about us—among them, for example, visual stories like those captured in the photographs taken by the colonial officer that is mentioned in the book. It was motivated by a desire to renew the transmission of stories that were not allowed to be transmitted. Those photographs that dictate our stories depict the Jewish girls from the Maghreb outside of their time, as [if they were] hangers for “traditional jewelry.” In my story, the girls are full of life; they are the daughters of those artisans who made these jewels and could have continued to make them if their world had not been destroyed.

JWA: You are also currently a professor of political theory at Brown University. What drew you to teaching as a career?

AA: Every semester I open my class with a statement that we are here not to learn, but to unlearn. I explain that despite the age differences between all of us, we were all born to a world that was imperially shaped, and we must unlearn almost everything that surrounds us, since most of it was shaped with violence. Unlearning together with others is what teaching is for me.

JWA: Do you have an ideal reader in mind for Golden Threads? What effect do you hope the book will have on its readers?

AA: The book is for children ages six to twelve. I love the idea that it will be read aloud by an adult to children at the age of six or seven, as I can anticipate many conversations around many things described in the book. I want to believe that those readers who are a bit older and can read by themselves will experience the book like a journey of discovering a world they are not familiar with. I would also like to believe that those readers who are descendants of the Jewish Muslim world may recognize along the way some familiar and dear objects that were passed on to them within their own families.