"Disobedience" and the History of Jewish Lesbian Obscenity

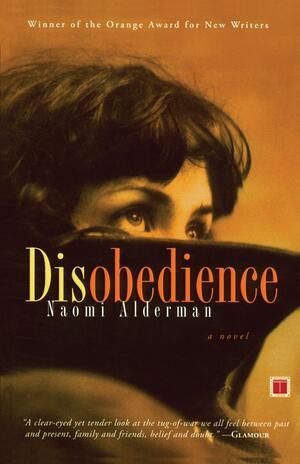

At its core, Naomi Alderman’s novel Disobedience, which was later adapted into a movie, is a story about two Orthodox Jewish women in love. Ronit, a formerly Orthodox woman who left her frum community to pursue a career—finance in the book, photography in the film—returns home to Hendon, London, on the occasion of her father, the rabbi’s, death. Upon her return, she rekindles her romance with her teen sweetheart, Esti. Esti, however, is now married to a sweet if uninteresting man named Dovid. Together, Ronit and Esti navigate love, Torah, loyalty, and betrayal—of each other, of their families, and of their communities.

Alderman grew up in the Orthodox London community she writes about, making her uniquely qualified to write this story. Her book, and the film adaptation by a non-Jewish director, were called groundbreaking: people said Disobedience was the first work of art to so explicitly depict women who love women within the Orthodox Jewish community. Then, in the same breath, the film in particular was accused of fetishization, and of portraying Jews in a negative light to the outside world.

Both these criticisms and praises may be true. Disobedience powerfully paints the rich inner emotional lives of women who are confused about their feelings for each other, and at the same time wish to hold on to their love for their community—beautiful traditions and ancient rules and all. It is also true that Disobedience, particularly in its film iteration, may reinforce stereotypes about Jews, and about frum Jews in particular, creating communities in which women are trapped and cannot fully express themselves.

Disobedience was lauded as the first story of its kind. But in many ways, it wasn’t new—and its criticism wasn’t new, either. If you wish to see a predecessor of Disobedience, you must look to the stage. Gut Fun Nekome (God of Vengeance), written by the Yiddish playwright Sholem Asch in 1906—exactly 100 years before the Alderman’s Disobedience was published in 2006—was a play about two Jewish women in love. It was a sensation in Europe, and then came to America in English translation.

In Gut fun Nekome, a brothel owner hopes to marry off his daughter to a respectable man—a rabbi’s son, a scholar—in order to give her a holier, better life than her parents had. But his daughter, Rifkele, is secretly in love with Manke, one of the women being prostituted by her father. The two women run off together, disobeying Rifkele’s father and trying to assert their own agency.

Gut fun Nekome was so popular that the English production ended up on Broadway by 1923. So, stories about Jewish lesbians aren’t new. They’ve been around, at least on the stage, for as long as depictions of any lesbians have. But God of Vengeance was not fated to spend long on Broadway; the play was quickly shut down on charges of obscenity. It was too Jewish, it was too lesbian, and the elite of 1920s New York couldn’t stomach a play that centered both of these taboo identities at once.

Not only are there plot similarities between God of Vengeance and Disobedience, but the backlash to each work of art mirrors the other, too. The play was condemned for simply being too much, both from within and outside the Jewish community, just like the film.

The Forverts reported on the God of Vengeance obscenity trial in their March 7th, 1923 edition: “Since the Sholem Asch drama began being performed in English, those dedicated to ‘defending morality’ are in agreement that the play is immoral and have sought means to suppress it. Finally, they were able to convince the District Attorney’s office to investigate and file official complaints against the actors and actresses, as well as the management.”

Many within the Jewish community saw the play as bad for the Jews. To them, God of Vengeance wouldn’t help a hostile world to see Jews as people but would instead showcase us as obscene. Rabbi Joseph Silverman of the Reform Temple Emanu-el in New York was one of the play’s primary enemies. The Jewish community could not collectively portray itself as a people with knowledge of such low and vulgar things as brothels and lesbians, Silverman argued. It would only make the gentiles hate us more. Rabbi Silverman—not the outraged goyim whom he feared—was in fact the one who brought the obscenity charges against God of Vengeance in the first place.

More than a century later, many reviewers rejected the movie Disobedience as “bad for the Jews.” Reviewers either fixated on the slight slip-ups in the “Jewishness” of the film (like a loaf of Challah, uneaten, on the kitchen counter on a weekday, or the fact that one of the actors couldn’t quite pronounce his “chet” right), or said that the film exoticized either Jewishness, or lesbianism, or both. My friends felt confused to see people like us depicted on film, and convinced that there was something fundamentally wrong with how this was done. Maybe it wasn’t Jewish enough, or it wasn’t lesbian enough, or the combination of the two was just two delicate a subject to put on film. This film, like God of Vengeance, was an obscenity.

We, as Jews, constantly police ourselves out of fear that we’re somehow presenting a fetishized version of Jewishness, or an incomplete picture, or a narrative that might reinforce stereotypes or turn people against us. Queer women do this too: We are afraid to present as too stereotypically masculine, afraid to profess our desire for other women for fear that we’ll come off as creepy or predatory. We have, after all, always been taught our love is obscenity. We guard closely against self-fetishization.

However, it is unreasonable to ask any piece of art to accurately and perfectly portray every aspect of a people. We cannot expect either God of Vengeance or Disobedience to be perfect representations of all it means to be Jewish, or of all it means to exist outside the boundaries of heterosexuality. If we let go of this expectation, we can appreciate both of these works, separated by a century, for what they are: just two stories out of all the infinite stories that could and might and do exist in this world about two people, who happen to be Jewish, who happen to be women, who happen to be in love.

Disobedience is one of JWA’s 2018-2019 Book Club picks.

Disobedience may have slipped a little in its portrayal of Jews and Judaism, but its portrayal of lesbians and lesbian sex was as authentic as Christmas carols at Hanukkah. The gaze was male. Not too many lesbians enjoy spitting from a distance into their new lover’s mouth. And sex standing up is more common in the gay male world than in the lesbian world and is an unlikely start for a new lesbian couple. These were probably attempts to make lesbians and lesbian sex “ virile”, like Christianising Judaism.

There's a lovely play called "Indecent" by Paula Vogel about the Sholem Asch play and the surrounding controversy that tackles this issue with amazing nuance