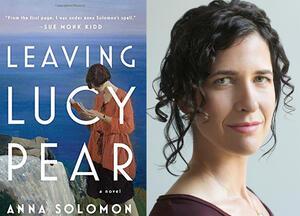

Anna Solomon on History, Motherhood, and "Leaving Lucy Pear"

Our May Book Club pick is Leaving Lucy Pear, by Anna Solomon. This historical novel takes place in New England in the 1910s and 1920s and follows a cast of characters whose lives are transformed by a teenage girl’s decision to leave her newborn baby in a pear orchard. I spoke with Solomon about mothers, history, and why 1920s America is not so different from our country today.

We chose this book for our May read because of Mother’s Day. Lucy Pear grapples with the theme of motherhood in poignant ways. How did you decide to engage with this theme for your book?

I don’t know that it was so much a decision as an upswell of obsession inspired by the lives of others and my own life. I think I’ve gone through, and maybe, am starting to come out of a fascination and obsession with what it means to be a mother, what is gained and lost through motherhood, and the ways in which we are and are not allowed to talk about that private experience. As I wrote Lucy Pear, I became more aware that I have one character who has abandoned her child, one who has more children than she ever would have wanted, and another who desperately wants children but is unable to have them. I never want my characters to be representations of anything, but I did recognize that I was playing with women who had very different but very fraught relationships to motherhood.

Your book takes place on Cape Ann, in Massachusetts, in the 1910s and 1920s. How did you pick that setting?

Gloucester, Massachusetts, my hometown in the Cape Ann area, continues to show up in my work. I feel very connected to it and shaped by it, and so in part there’s just an instinct to write about that place. One of the seeds of Lucy Pear was a book of history that I found about a woman who was summering in Gloucester and suffering from a nervous disorder. She asked that a whistle buoy be taken out of the water because it was disturbing her. Reading about that incident made me definitively decide to set the book in Gloucester. And then as the story took shape, other aspects of the place continued to ground it, and necessitated that I set the book in the 1920s as well: the history of Gloucester’s quarries, issues around labor and strikes, and the trial of Sacco and Vanzetti. All of that was necessary to that time and place. The process of writing and research is very symbiotic for me. I write something, it leads me to certain research, which leads me back to the writing. At a certain point, they become inextricable from each other.

What is it about historical fiction that attracts you?

I’m very interested in the gaps between what is known and what is actually lived, between the public record and private experience. This is something that you can write about in a contemporary or futuristic setting too, but I think writing history or historical fiction allows for truly productive exploration.

I’m also interested in how on a fundamental level, human consciousness is universal. Even though we come from different cultures, the basics of what we want and what we fear are shared. Going back to other periods lets me explore this, and also argue for it, in a way. To me, the story and the characters come before the time period.

Also, the fact that both of my novels take place in the past has given me permission to write plots that feel bolder than I might have felt comfortable writing if they were set now. That’s been freeing for me. The short stories I have published are more contemporary, and it felt like moving back to a different time gave me the courage to make a big leap plot-wise.

What are some other settings and historical stories that you might write about in the future?

The book I’m writing now weaves three different periods together. One is contemporary, one is the 1970s in Washington, D.C. and in Massachusetts, and one is ancient Persia.

What I’ve found about ancient Persia is that almost everything is arguable and no one knows anything. It’s freed me up. I’ve done research, but I’ve also allowed the narrative to acknowledge the limits of historical fiction.

The 1920s were perhaps not as different from today as some might think. What can we learn from reading about that time?

I have to say that when I started writing Lucy Pear, I wasn’t that conscious of the fact that that decade looks a lot like our own time. I think that’s because when I started writing, a lot of the forces and extremities that have come forward in the last few years were not as explicit. Certainly in the lead up to the election, and the aftermath of the election, I thought about the similarities to the 1920s and thought, oh, wow. And not in a positive way.

When I was first drawn to the 1920s, I have to admit that I came to it superficially. I was thinking about the more glamorous side that I’d seen in movies and books: the flappers, the booze swilling. As I wrote and researched, I came to understand what a dark decade it was, in terms of the politics and what I think of as a post-war mentality. Now, I think we’re living in this perpetual post-war mentality: this fear of the other, this sense that we are in danger in some way. The anti-immigrant, white-supremacist sentiments that were dredged up after World War I––we see that today. And I don’t know what we should do. I do know that I take some comfort in the fact that we kept working as a society towards justice, and that we’ve made some progress since the 1920s. In my book, the character Albert is gay, and he is subjected to a secret court at Harvard that’s intended to suss out and expel students engaged in homosexual activities. That was based on something that actually happened. I know many of us feel like we’re going backwards; I try to hold onto how far we’ve come.

Leaving Lucy Pear is a JWA Book Club pick; see our discussion questions for the book.