After a lifetime of silence, Deborah Strobin shares her story

Deborah Strobin is a well-known Nob Hill, San Francisco philanthropist credited with organizing large and high profile fundraising events over the past two decades, including the first ever HIV/AIDS benefit at Davies Symphony Hall in the 1980s, the city’s first Yves St. Laurent couture fashion show to benefit the San Francisco Symphony, and the largest fundraiser in US history for stem cell research in 2006. Deborah also served as the Deputy Chief of Protocol for the city of San Francisco and commissioner of the Public Library Commission.

For most of her life, philanthropist Deborah Strobin kept her past a secret from her friends, her children, and even her husband. It wasn't until she visited the Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C. and came face to face with photos of herself as a five-year-old refugee in Shanghai's Jewish ghetto that she finally decided to tell her story.

From 1938 to 1945, Shanghai was the only city in the world that accepted Jewish refugees from Europe without exception. Even though the Jewish refugees of the Shanghai ghetto shared in the hardship and deprivation imposed on the Chinese by their Japanese occupiers, the Shanghai Jewish community was one of the only refugee communities to survive the War intact.

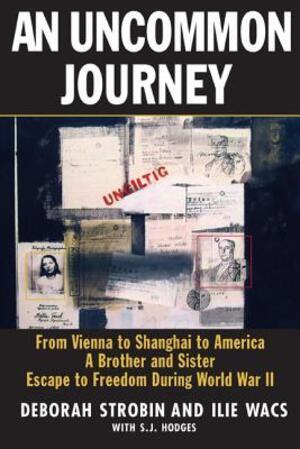

Born in Vienna, Deborah Strobin and her brother Ilie Wacs escaped Nazi Austria along with their parents on the last boat to Shanghai during WWII. Their oddessy is captured in a new memoir entitled An Uncommon Journey--From Vienna to Shanghai to America: A Brother and Sister Escape to Freedom During World War II. Written from two perspectives, that of a teenage boy eager for adventure and a young girl whose parents are determined to keep her innocent and protected, An Uncommon Journey is a three-dimensional picture of the harsh and chaotic reality of life in the Shanghai ghetto.

Today Deborah Strobin is a well-known Nob Hill, San Francisco philanthropist credited with organizing large and high profile fundraising events over the past two decades, including the first ever HIV/AIDS benefit at Davies Symphony Hall in the 1980s, the city’s first Yves St. Laurent couture fashion show to benefit the San Francisco Symphony, and the largest fundraiser in US history for stem cell research in 2006. Deborah also served as the Deputy Chief of Protocol for the city of San Francisco and commissioner of the Public Library Commission. Her late husband, Ed Strobin, was chief executive officer of Banana Republic and one of the founders of Discovery Channel stores.

We at JWA were excited to have the opportunity to find out more about Deborah's experience of telling her story after so many years of silence.

Q&A with Deborah Strobin

JWA: What was it like to discover a photograph of yourself at five years old at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C.?

Deborah Strobin (DS): It is hard to describe the exact feeling. It felt like an out of body experience, shock, sorrow, guilt. At first I felt so sorry for that little girl with those sad eyes until I realized that little girl was me. Immediately there was a connection, and my past caught up with me.

JWA: You kept the truth about your childhood from your husband, friends, and your sons. Why did you choose to share your story now?

DS: I would say that seeing the photograph at the museum planted a seed that needed to thrive. It took years for me to finally free myself of the shame I felt being stateless and at the mercy of others dictating my destiny. I did not know anything about my background that made any sense and felt that my children deserve to know their true heritage.

JWA: What was it like to work on this project with your brother, Ilie? Was he as private as you about your family history?

DS: Working with my brother was a true learning experience. He exposed the fallacy that in a way protected me. My parents tried to protect me from the horror that they endured which isolated me from reality; hence I embraced the fantasy that I invented. Ilie was not private about our family history to the outside world. In fact, I would say he was in your face about it. We never talked about our past until we collaborated in writing this book.

JWA: Do you feel differently now that your friends and family have been able to share in your remarkable story?

DS: Yes! I was able to let go of my past and concentrate on the future knowing that my children were able to digest all the information and accept their heritage with pride. I felt free for the first time, and hiding was no longer an option.

JWA: In what ways have your family's history and your experiences during the War informed your longstanding commitment to philanthropy?

DS: Having been deprived of freedom, and having to live for the hope of tomorrows that may never come, does instill compassion for others. It reminds me of the times I prayed that if I was good, nothing bad would happen to me and my family. Raising awareness for many causes that are not considered sexy (pardon the expression) such as AIDS, cancer, obesity, the homeless, gives me hope that my efforts, along with commitments from others, will someday make a difference and perhaps will be a launching pad for making magic happen.

I read your book, An Uncommon Journey, with utter fascination. It was so interesting seeing the differing points of view of you and your brother. I couldn't put the book down. I read until 2 in the morning when I couldn't keep my eyes open any longer and then finished it as soon as I woke up the next morning.

I would love to hear you and your brother speak. Are there any future dates when you will be speaking?

Yours truly,

Eileen Olicker