The World As It Is: Learning To Read Adrienne Rich

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

—Adrienne Rich, from Diving into the Wreck

When I think of Adrienne Rich, I think about the differences between maps and routes, between shortcuts and whole geographies. I think about the difference between following directions that lead you straight from A to B and sitting down with your Atlas of the Difficult World with no destination yet in mind. I think about trying to take in all that maps have to tell you with your heart and eyes open, about looking to learn without knowing what you will find or where this new knowledge will lead you. When I think about Adrienne Rich, I think of the different ways we learn, the different ways we come to know the world, ourselves, and vice versa.

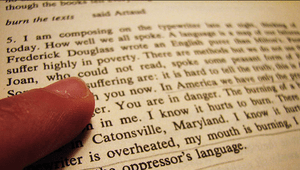

I first encountered Rich’s writing in 2006, my sophomore year of college, in a class on twentieth-century American poetry. It was a survey course, a challenging one, but because I was not yet ready for most of its challenges, I took many of the shortcuts that surveys are obliged to offer. My shortcut into Rich’s work was, I expect, a relatively common one: I read “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” Rich’s famous 1980 essay on the patriarchal suppression of women’s thoughts, relationships, and sexuality, alongside selections from her early book, Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law (1963) and later poems from Diving into the Wreck (1973). As a class, we discussed the translation of social oppressions into poetic forms, the determining constraints of meter, rhythm, and rhyme, and the liberatory power of rejecting these forms. We talked of excavating the outlines of a different poetic self through the lyricism of free verse and the choice of different metaphors and histories. I learned to use phrases like “the lesbian continuum” and words like “re-visioning.” I fashioned for myself a quick and naive one-to-one-to-one equivalence between Rich, lesbian feminism, and poetry.

There is nothing inherently wrong with shortcuts—they are necessary to navigating the world, to forging paths through the pressures of time and space—but often they allow us to ignore whatever seems extraneous to the journey we already have in mind. They let us overlook complexities in favor of easy knowledge, and, therefore (as I would later learn), shortcuts are antithetical to Rich’s poetics, her politics, and her ethics, three intertwined aspects of her thinking that cannot be reduced to any simple or static equivalence.

I was ten years old when Rich famously refused the National Medal for the Arts in 1997, writing in an open letter to President Clinton that “There is no simple formula for the relationship of art to justice. But I do know that art—in my own case the art of poetry—means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table of power that holds it hostage.” Taken as a sound byte, so to speak, this moment, like many in Rich’s career, can be understood relatively easily. I can focus on what she declares to be known—that Art is meaningless when it is subordinated to the power that holds it hostage—rather than what, for her, remains unknown: the relationship of art to justice.

But Rich’s work refuses to settle for what we can know, choosing again and again the exploration of uncertain territories. She is a poet of questions rather than answers, a poet “long engrossed” in “the study of silence,” a thinker for whom listening is the greater part of speech. Consider the opening lines of “Yom Kippur 1984”:

What is a Jew in solitude?

What would it mean not to feel lonely or afraid

far from your own or those you have called your own?

What is a woman in solitude: a queer woman or man?

In the empty street, on the empty beach, in the desert

what in this world as it is can solitude mean?

When I read Rich’s poems, I resist the urge to leave the questions. I dwell in them and they open up around me: what can solitude mean when our identities are formed in community? When we know ourselves through how we relate to those with whom we share a religion? With whom we share similar desires, desires perhaps contained in similar bodies, or perhaps not? What is this “world as it is,” and how can I come to know it well enough to take the further step of reckoning with what solitude may mean for me, or for you? I find all these questions in a single poem.

Even though Rich was alive and writing when I first read her work, I was introduced to her through her role in a particular history. I learned to see her as a part of the past that has formed our present. When we die, we lose whatever ability being alive grants us to explain ourselves on our own terms, to revise, to recontextualize, to transform ourselves again and again. After our deaths, this becomes the work we leave to those who follow after us.

Thinking about Rich today, I am left with many questions. One of the largest is this: I wonder what Rich will mean to my generation of women, women for whom her world-changing essays and poetry have always been available, for whom the vocabularies she discovered have always been a part of what we can say, see, and know about the world. I do not know the answer to this question, though I hope there will be many. I do know this: I have learned from Rich that you can come of age as a feminist, as a poet, as a woman, as a Jew, at any age—that if you are living your life fully and openly, you will likely come of age many times. I have learned that when we are lucky, shortcuts are entrances to the long way around in disguise. A single question can reopen landscapes we thought were familiar, and Rich’s poems ask us to go there, our maps yet to be written, ready to reimagine what it is possible for us to see.