50 Years On: 5 Things I Learned About the March on Washington

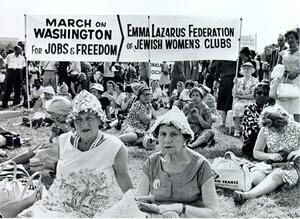

As a kid I read everything there was to read about the Civil Rights Movement—from the Freedom Rides, to sit-ins, to Freedom Summer. I wrote my biggest high school term paper about the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, and the closest thing to a history class I took in college was called simply, “The Sixties.” But it wasn’t until I saw this photo of women at the March on Washington wearing pearls and sunhats under the banner of the Emma Lazarus Foundation that it occurred to me: there were Jews at the March.

In honor of the 50th anniversary of the March tomorrow, I would like to share 5 things I have learned about the March on Washington that you may not already know—one for each decade. I hope you’ll take this opportunity to check your assumptions and look more closely at this monumental, game-changing event.

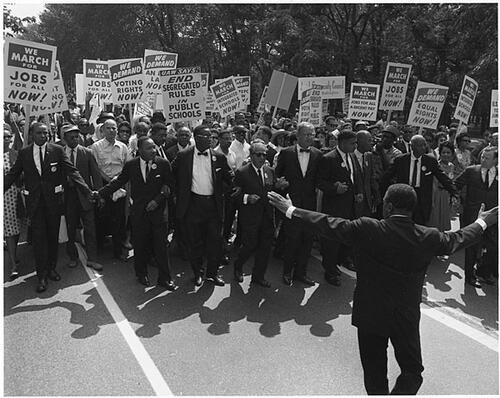

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

As the signs in this picture suggest, protesters at the March had different motivations for being there. The March was actually the brainchild of A. Philip Randolph, a labor leader and civil rights activist who was the Vice President of the AFL-CIO. Randolph had originally proposed a March in 1941 to protest the exclusion of black workers in wartime industries but the March was averted when President Roosevelt allowed blacks to work in military factories.

Twenty-two years later, Randolph convened leaders from all of the major Civil Rights Organizations—Whitney Young of the National Urban League, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, James Farmer of Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Martin Luther King, Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)—to support another March. This broad backing encouraged the White House to allow the March to continue. As Unions and religious organizations joined the effort, some groups leaned more toward the “jobs” goals and other toward “freedom,” but they formed a cohesive and unified group that ended up being the largest gathering of people in U.S. history.

There Were Jews at the March

Well, this isn’t so surprising—there are Jews in most places.

There were five Jewish leaders on the platform the day of the March including Rabbi Uri Miller of the Synagogue Council of America who gave one of the opening prayers and Rabbi Joachim Prinz of the American Jewish Congress who delivered one of the speeches.

Rabbi Prinz drew lessons from the Holocaust to illustrate the importance of justice and the pursuit of civil rights. You can listen to his speech in the Civil Rights module of Living the Legacy.

A Jewish musician, Bob Dylan, played music during the March (I love watching the footage of his performance with Joan Baez). They were joined by thousands of other Jews on the Mall including groups from the National Federation of Temple Youth (NFTY), the Central Conference of American Rabbis, and the Emma Lazarus Federation.

There Was a Logistics Team

One of the best things I have seen come out during the commemoration for the 50th anniversary is this series of videos from TIME called “One Dream.” In the second part of this short series, activists and organizers highlight the logistical end of organizing the March.

Rachelle Horowitz, the Transportation Director, describes chartering every bus, train, and plane they possibly could in order to get people to the March. Singer and activist Harry Belafonte even chartered an airplane from LA to DC to bring big name actors like Burt Lancaster, Paul Newman, and Marlon Brando to the March saying, “I understood that wherever I could use the platform of culture and the arts and put it at the service of Dr. King…became part of what I had to do.”

SNCC volunteer Doris Derby remembers recruiting volunteer doctors and nurses to be on-call to provide medical care and Julian Bond describes the volunteer marshals who provided security among the nonviolent demonstrators to avoid confrontation with military or police personnel. Other volunteers assembled the approved signs that were specifically created to send a message of unified support of the Civil Rights Act.

John Lewis’ Speech was Almost Pulled from the Program

John Lewis was the head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and in the true spirit of that organization, wanted to push the envelope and call people to action in his speech. The Kennedy Administration and several members of the March committee felt his speech went too far and demanded Lewis censor what he wrote, but he and other SNCC members refused.

Finally, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, A. Philip Randolph approached Lewis and asked him again to make the change saying, “John we've come so far together, let's stay together. For the sake of unity make these changes...”

Lewis’ response? “You couldn't say no to A. Philip Randolph." (Quoted in NPR report, “Behind the March on Washington: A 40th Anniversary Look at the Struggles to Stage the Event,” August 22, 2003.) While Lewis gave his speech, the changes alienated many radical activists. You can read excerpts of his speech, and see the pieces that he omitted, here.

There Were No Female Speakers at the March

Though several women sang at the March on Washington, none were invited to speak. Women leaders, of course, attended the March and several, including Rosa Parks, lawyer and feminist Pauli Murray, and student coordinator of the Freedom Rides Diane Nash, demanded that women be a part of the program—but the male organizers refused. In a 2007 article from the New York Times, Dorothy Height, President of National Council of Negro Women, recalled, “Nothing that women said or did broke the impasse blocking their participation. I’ve never seen a more unmovable force.” Unfortunately, this was reflective of the treatment of women—white and black—within the civil rights movement. Women were expected to take desk jobs and do clerical work. Others played integral organizing roles or put their lives on the line demonstrating and doing voter registration—but were never treated as equals.

The irony of this double standard, working for racial equality without having gender equity, was not lost on the women of the Civil Rights Movement. This was a motivating factor for many women activists who decided to take up the causes of the feminist movement.

So Here We Are and Now You Know

This year as you look back at pictures, listen to testimony of people who were standing on the Mall, and watch Dr. King’s speech—over and over again—I want you to remember why we celebrate this day. Remember the speeches, but remember also the women under the Emma Lazarus Foundation Banner. Remember the women activists who sat silently on stage as A. Philip Randolph spoke about their hard-earned triumphs, and remember that the main reason we can celebrate tomorrow is because 250,000 regular people decided it was important to show up and be counted.

Excellent information and great writing! Thanks so much for this reflection.

Wonderful article. Thank you for all this info and reflection!

starofdavida.blogspot.com